Summary

Is your company prepared for a volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) world?

Many challenges faced by businesses today are brand-new and require a fundamental rethinking of how best to respond. This is difficult in traditional business environments, where hierarchical structures still exist in the same way they have done for decades, and we use the same problem-solving methods that our great-grandparents may have used in their businesses. In a VUCA world, where decisions may need to be made quickly, and balancing several relevant contexts, Moving Organizations provides new, agile methods that increase your chances of achieving successful and lasting change in your business.

Written in an easy-to-understand way for the busy executive, Moving Organizations provides a basic understanding of agile transformation methods and an orientation framework for change strategies, to help you bring order into the chaos of tool diversity. Featuring real-life case studies to help ground your learning in practice, this helpful guide will have your business confidently facing any challenge.

This book…

- Helps companies to develop robust and coherent change strategies for a VUCA world.

- Features real-life case studies to provide a practice-oriented approach.

- Offers new scientific findings for dealing with the emotions associated with change in a VUCA business environment.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

1 Moving organizations

1.1 On the goal of remaining flexible and crisis-proof

This book is about the transformation of companies and organizations—a transformation that is becoming necessary in order to keep pace with the complex demands of the market and society. Until now, organizations mostly operated in largely stable environments and were able to anticipate developments. This enabled them to buy, produce, sell and plan and to become more and more efficient in all of this. Efficiency was their focus. Like a competitive athlete who sets the bar higher and higher or runs the same distance faster and faster, organizations were able to become better and better, that is, more efficient, over many decades. This is why today we purchase products and services that are much faster, cheaper and more efficient than decades ago.

But the world has become more unpredictable and complex. The big challenge for organizations today is to cope with a high degree of uncertainty and complexity. Instead of being able to devote themselves primarily to improving and increasing the efficiency of their services or products, they must now primarily try to get to grips with this uncertainty and complexity and work with it. Digitalization has driven these changes, and the Corona crisis has accelerated them enormously.

Crises are, by definition, turning points. The great crisis triggered by the Corona pandemic has presented the world with completely new challenges. Such crises cannot be mastered without well-functioning organizations, which have to bring their full potential to bear, often reaching and even extending beyond their limits. Organizations that already knew how to use digital media sensibly during the Corona crisis were at an advantage, others tried to follow suit as quickly as possible. In the meantime, modern digitalization strategies have become part of the basic equipment of every organization and continue to drive change within it.

Some organizations proved able to act even in the middle of the crisis. They had already planned buffers in advance, established stable processes and prepared their staff. They were resilient, that is, prepared for the problem and able to survive the crisis largely unscathed. We will discuss the characteristics of resilient and thus crisis-resistant organizations in more detail later.

The digitalization of processes is accompanied by an increase in complexity within organizations. More and more options are available in ever less time, and at the same time there are hardly any routines and empirical values to fall back on in individual cases. This increase in complexity is a major problem, especially ←11 | 12→for decision-makers. They have to decide on a multitude of options in a short time without being able to fall back on tried and tested decision-making aids. This shifts their focus and the focus of the whole organization. A huge change!

This book is about how such a transformation can succeed. It is about the transformation from “efficiency” mode to “agility” mode. Because if organizations want to be crisis-proof, they must above all be able to make decisions quickly despite complexity, and they can do that if they are agile. In the time of the Corona crisis, it was easy to observe which companies were able to change quickly and adapt their services—including state organizations. Which is not to say that agility automatically has to come at the expense of efficiency—one does not exclude the other. But it is primarily agility that guides a company through uncertain times.

“Agility” is another word for playability. Agile organizations focus on staying playable. This objective determines how they work, what tools they use, how they decide and distribute power. The term “agility” thus encapsulates all the initiatives that organizations develop to capture complexity.

The process, the transformation to get there, is a challenging journey and this book is a travel guide for all organizations that want to go down this path of transformation. We want to show you how such transformations can succeed. Walk through the different stages with us: We report directly from our practice and embed it in theory in such a way that you can deepen your understanding. We will demonstrate why it is especially important now to use a good framework to make good decisions. We invite you to take short excursions into history and explain how and when some concepts originated. You may also be surprised where ideas first originated, why they were forgotten for a while, and why they resurface today. We also introduce you to our practical tools and instruments.

More than ever, organizations are exciting places. Places where important things can happen for people and society, but only if this is wanted and if the right skills are developed for it. We would like to contribute to this. We would like to invite you to do so.

We are particularly concerned with connecting the steps, with painting the big picture. You use a tool differently when you know the associated model and have thought through the context and theory in which everything is embedded. Too often we have seen processes fail because their primary focus was on the use of tools and the overall context was lost. But if you know the context, if you learn to climb from the lowlands of practice to the heights of the models and abseil down again, if you know what the assumptions behind the approaches are, you will be much more successful and will enjoy the path of agile transformation.←12 | 13→

The starting point of our journey is described in six hypotheses in the first chapter. These are assumptions about how we understand digitalization, agilization, crisis resilience and change in organizations today and how organizations relate to society. Then, in a separate step, we derive the special requirements for transformation processes and show how these differ from earlier procedural models. An example from our consulting practice illustrates how we proceed.

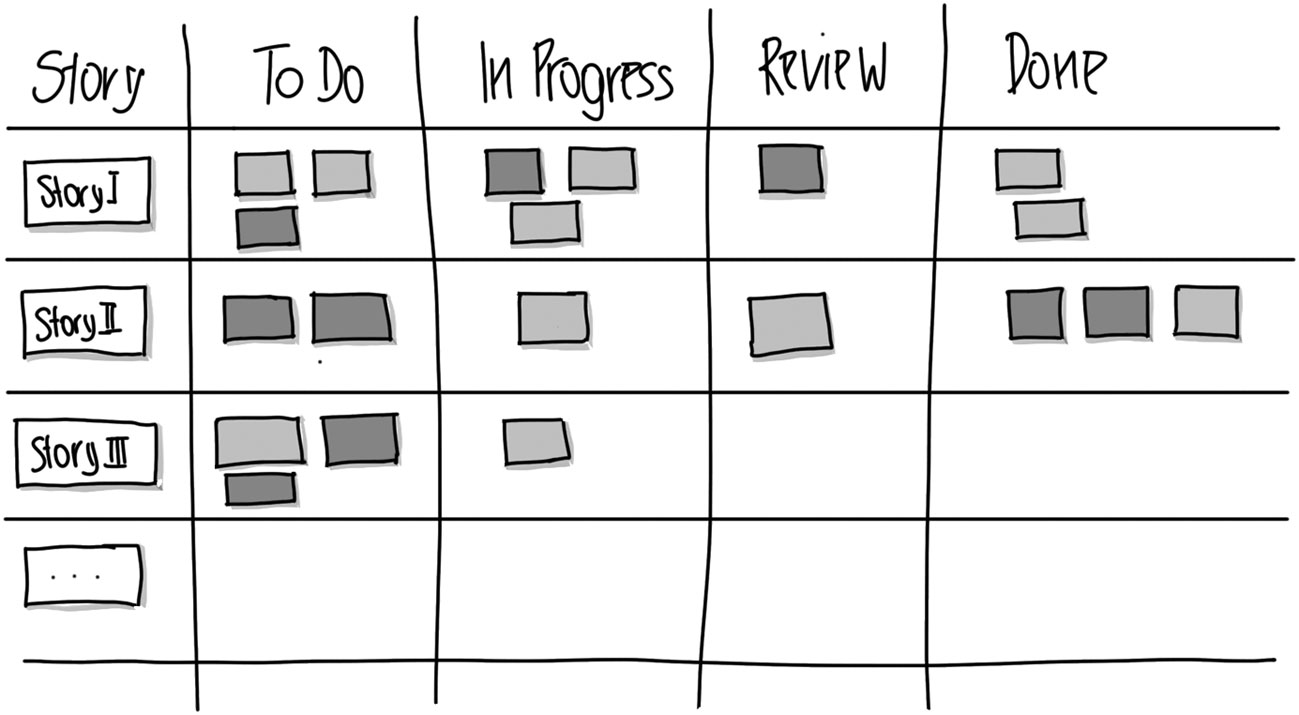

The second chapter begins with the example of a service team in crisis and describes the capabilities that organizations need in such situations. For decades, resilience research has been investigating what distinguishes robust organizations, that is, organizations that cope better with crises. However, the results were long overshadowed by the debates on agility until the Corona crisis suddenly made them red-hot. Surprisingly, the two concepts of organizational resilience and agility are not very different. We compare both approaches and offer the Tension Square as an orientation framework to help you locate your own organization. This will help you find the starting points that you can practice so that your organization is equipped for a successful journey. Furthermore, this second part describes agile tools for project work and the model of an agile organization: the holacracy. The chapter is rounded off with the systemic perspective, that is, how much the systemic view will benefit you in times of crisis and high complexity. And as in the first chapter, we conclude with a case study from our consulting practice.

The third chapter is dedicated to the nine levers of agile transformation. These have proven to be particularly important for us in the context of the transformation of organizations. The fields of transformation, such as working in teams, culture, role design, skills of individuals, leadership, power and purpose are examined in more detail. Our way of working is also explained here by case studies.

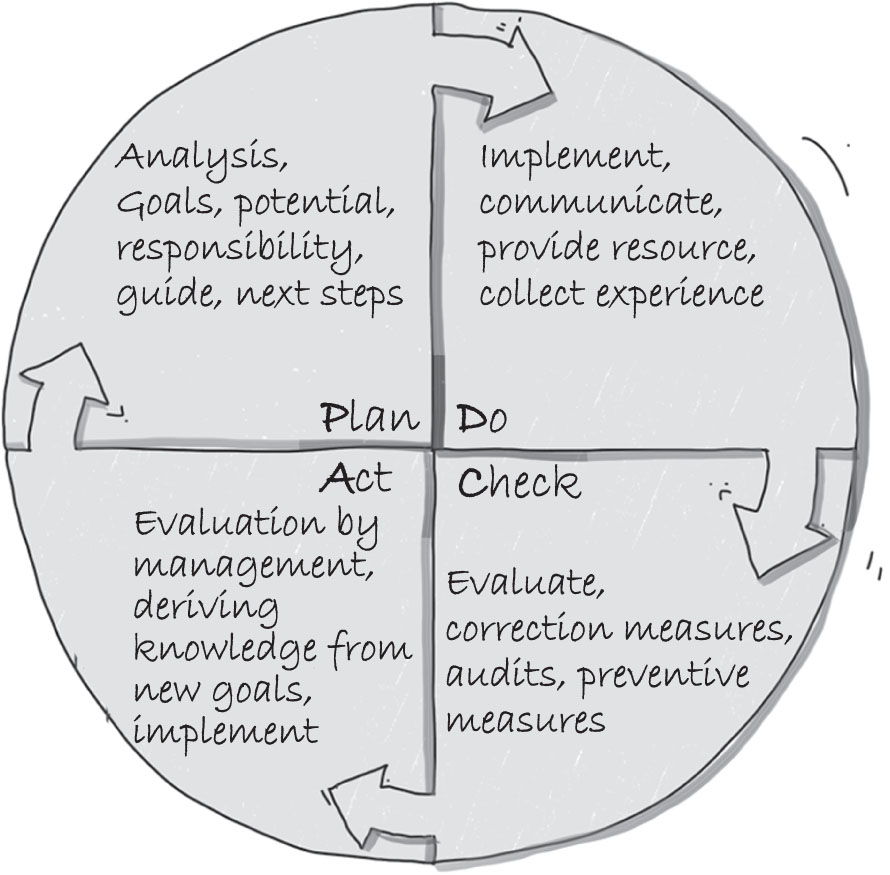

The fourth chapter is about the process of agile transformation. Here it becomes clear how we work in transformation, how interventions are planned and used. For this we use models, also called power tools, which have a strong impact and show what difference they make for us compared to common practice. Our concern is to place concrete procedures in a larger context and to link tools to the process and effects.

Finally, the last chapter is devoted to tools. Practitioners and counsellors will find over 40 tools here that we have successfully used in transformation processes. The purpose, the conditions for use and a direction are described for each tool and cross-referenced to the corresponding chapters in the book. We recommend reading these before using the respective tool.←13 | 14→

1.2 What moving organizations is all about

The title of this book, Moving Organizations, owes much to the fact that organizations today are on the move more than ever before. By organizations we mean not only companies but also public authorities, non-profit organizations or associations. The movement varies depending on the sector or area of society, but standing still is no longer an option. Organizations and their employees have to cope with it and make sense of the movement. Moving organizations are able to move, touch and engage employees. Organizations can be places that create meaning, that help to develop people and that contribute to social development. We find it desirable to create moving organizations that are mobile and also crisis-proof.

Crisis resilience—especially when viewed in the light of recent history—is a primary goal if organizations are to survive for long. In order to survive, organizations have to perform, but the conditions under which they do so have changed massively. We have, therefore, chosen the term “moving organizations” for those organizations which

• work on their agility and resistance to crises, and thereby become resilient;

• give special priority to the development of employees; and

• consciously take on their social role.

Moving organizations are organizations that keep moving by changing many things at once. They know that this is not just a phase of change followed by a period of calm and stability, but that the next, as yet unknown change is already waiting. The basic idea of change management was quite different: unfreeze, change, freeze again. Instead of thinking of change in phases, it is now important to understand it as a movement, as a swarm of individual changes that influence each other.

Moving, that is constant movement makes different demands on the members of an organization and influences their relationship to the organization. In order to be able and willing to participate in these movements, more is needed than just a purely factual relationship along the lines of “service for remuneration”. It also needs an emotional agreement between the employees and the organization, their relationship has to get out of the end-means logic, where employees or the organization are means for the ends of others. This is also the thinking behind the strange expression: “work-life balance”. Does that mean that we work for money but our lives take place in our free time?

In a moving organization, we want a different quality of encounter. In this sense, organizations must be able to touch employees and they must open up and ←14 | 15→get involved. Only then can the trust and security arise to cope with this mixture of opportunities and excessive demands. Moving thus creates some security in change.

1.3 Six theses that move organizations

Most of us spend a large part of our lives in organizations and they are of great importance for our development and well-being. We are born in hospitals, learn in schools and universities, work in companies, authorities or NPOs, get involved in associations. Have you ever thought about which and how many organizations have been really relevant for you in your life so far?

Organizations inspire us. We think this “institution” is great and believe that we and society owe a lot to it. We ourselves found our dream job in an organization that specializes in the development of organizations. As a result, we know many very different types of organizations and also the challenges they face. The starting point and the motives are very different, but they all face a big challenge: They need, more than ever, to transform themselves. Digitalization, increasing complexity and crises are forcing them to do so. It is time for the transformation. For this, it is important not only to work in them, but also on them.

We believe that working on organizations is important not least from a societal perspective. Good organizations are important not only for the individual, but also for the community, because much that is socially relevant arises in organizations: Scientific research, new vaccines, film and music services, care and support services, platforms for finding partners. Practice shows that new ideas only become relevant for society when organizations take them up. We see this with the environmental movement, which had to found associations and parties in order to become effective. From these assumptions we derive our credo: Organizations are hugely important and we can shape them. This is our motivation, our purpose for writing this book.

To work with organizations, one should understand them and the current context in which they operate. From our point of view, the most important theses for moving organizations today are:

1. Digitalization is forcing organizations to find new responses to cope with greater complexity.

2. Agility is a social innovation that organizations use to counter increasing complexity. One of the ways they do this is by acquiring virtual competences.

3. In transforming organizations, one of the biggest hurdles is the redistribution of power.←15 | 16→

4. More and more people want to work differently and develop in the process. Moving organizations need exactly that and are responsible for creating the space for this development.

5. Preparing for and managing crises is part of the daily business of organizations.

6. The likelihood of crises increases due to greater interconnectedness and rising interdependencies, and organizations will be increasingly called upon to make their contribution to social development (common good).

1.3.1 Thesis 1: Digitalization is forcing organizations to find new answers1

In 1890, electricity replaced the steam engine as the power source in factories. Engineers bought the largest electric motors available on the market and replaced the steam turbine, which was in the middle of the machines, with the new motor. Little changed in the production process: The space concept, the way of working and productivity remained similar. Thirty years later, factories were unrecognizable. Instead of one big machine standing in the centre, there were many small electric motors. The spatial concept had changed completely. The work units were divided and women workers were divided according to material flow and workflow.

A new form of organizing was needed. Factories needed the arrangement of machines in the form of production lines, which analytically broke down work processes into their individual steps in order to structure them according to economic aspects. This would have been unthinkable in a factory run by steam engines. The new arrangement required a different way of thinking and was a social innovation. It was this that made effective use of an electrified factory possible in the first place. This form of social innovation is called Taylorism, which in its extreme application also had many negative social effects. Consequently, the technological innovation of electrification needed the social innovation to become effective. It then took another almost 100 years before electrification could fully develop its actual effect.

The change brought about by digitalization is no less profound. Digitalization is an innovation that necessitates social change in a co-evolutionary process. We call this social innovation agility. It is related to and dependent on the technological innovations of digitalization. Agility develops new forms of cooperation, but also creates new conflicts. It requires other social mechanisms and a new distribution of power (see also thesis 3 in Section 1.3.3 and lever 7 in Section 3.7).←16 | 17→

Therefore, it is worthwhile to better understand social innovations: “Social innovations are new practices for coping with societal challenges that are adopted and used by affected individuals, social groups and organizations” (Hochgerner, 2013). The challenges posed by technological change, therefore, need new social action, different patterns of behaviour, new types of communication and cooperation so that the potential of technological innovation can fully unfold. Social innovation is thus at the same time a prerequisite, a concomitant and a consequence of technological innovation.

Technical and social innovation are thus closely linked. Many things are not clearly defined, such as sequence, boundary and allocation. A prime example of this is the emergence of the World Wide Web: To enable women scientists at CERN to communicate and research more efficiently and globally, they sought new solutions. The development of the World Wide Web satisfied diverse social communication, relationship and cooperation needs through networked websites and thus through the networking of knowledge and information. The explosive spread of the World Wide Web, along with its technical development, came about in a co-creative and co-evolutionary process of social and technological innovation.

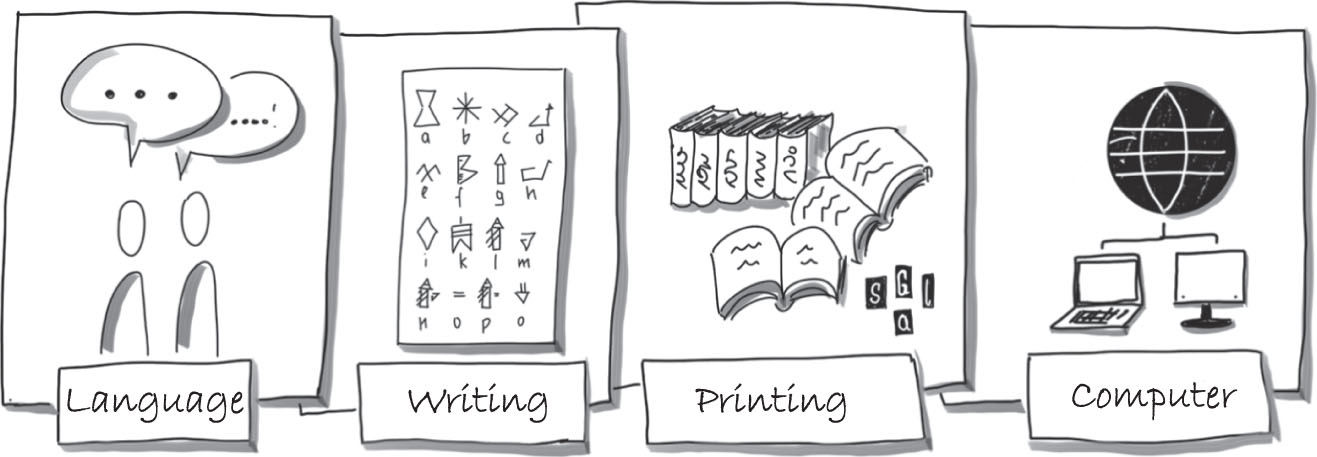

The most far-reaching innovations are those that target communication and knowledge in a society and bring about profound social changes. So far, we can reconstruct four such epochal innovations in human history (Baecker, 2007):

1. Language: The development of language enables a community to organize itself in tribal structures.

2. Writing: The invention of writing enables people to organize themselves into city-states and kingdoms.

3. Printing: The invention of printing enables the enlightenment of broad sections of the population and leads to the formation of nation-states and democracy.

4. Computer: The development of the computer and its networking through the internet enables a global society, new possibilities of communication and cooperation.

Fig. 1.1. Social innovations in history

Digitalization is another far-reaching innovation that deeply intervenes in our society in many ways. The effect of this intervention could be clearly seen during the no-contact period in the Corona crisis. Where physical contact was not possible, there was a switch to virtual communication. Those who could not but needed contact with others had a problem. All those who had to work from home set themselves up according to their technical possibilities and, after an initial phase of shock, found new ways of communicating. Not only streaming ←17 | 18→services for films, podcasts or online yoga courses saw a surge in demand, but also professional contacts and meetings, even the exchange of information and decision-making meetings in management boards and government bodies took place virtually. What had only taken place sporadically before the crisis and was often viewed sceptically, suddenly took off of necessity. People and organizations took hold and began to use virtual media. However, this phase also had another side. Many were overloaded and annoyed, for example, because they were overwhelmed by the many virtual meetings, because details were very difficult to discuss and there was hardly any opportunity for informal, personal exchange. Boundaries that provided support became blurred.

We are constantly experiencing how digitalization increases the complexity around us. Our world is not only becoming more complicated, it is becoming more complex. Complicated things can be systematized and learned. In a complicated structure like the London Underground with over 400 kilometres of track and 270 stations, you can find your way around after a while. Complexity, on the other hand, cannot be deciphered and extensive study and patience are of little help. Interrelationships are no longer clear, the same causes have different effects, many things are interrelated, and yet elements act independently of each other. Predictions are difficult and long-term planning impossible. The result is a world for which a term has been coined: VUCA-World (German: VUKA-Welt). Its factors are Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, Ambiguity. VUCA refers to a world in which many things are constantly changing, unpredictable and ambiguous. The VUCA world is a different “game” and requires different responses from organizations.

In the crisis, digitalization showed that it opens up new possibilities that would not exist without it, while at the same time increasing complexity. ←18 | 19→Organizations that had made sure in time that their IT infrastructure was well positioned by enabling cloud-based working, video conferencing and the necessary line capacity were more resilient in the crisis. In the wake of the Corona crisis, the proof was in the pudding: Digitalization helped make organizations more resilient.

While organizations in recent decades have strived to improve their efficiency above all else, today the focus is on agility and resilience. In a complex, unstable environment, it makes no sense to make organizations as efficient as possible, that is, to introduce routines, streamline processes and focus everything on working more cost-effectively. This means introducing routines, streamlining processes and gearing everything towards working more cost-effectively. The main thing now is to stay in the game. And to achieve this, organizations have to change from the ground up. Agility means: Playability comes before efficiency.

1.3.2 Thesis 2: Agility is a social innovation

Digitalization is a revolution, a game changer, especially for the world of organizations. They are confronted with more and more possibilities that are permanently changing. To deal with this, organizations need agility and thus social innovation. It is not primarily about the introduction of tools and methods, it is about a completely new form of organizing that replaces the system of Taylorism and the idea of efficiency, because digitalized organizations tick differently: They plan and lead in a more decentralized way, demand more from individuals and strive to renew themselves socially on an ongoing basis. Agility describes both the way there and the result—the constantly reorganizing organization. Agility, one could say, is the “new guiding idea for the restructuring of existing organizational relationships” (Schumacher & Wimmer, 2019, p. 12ff).

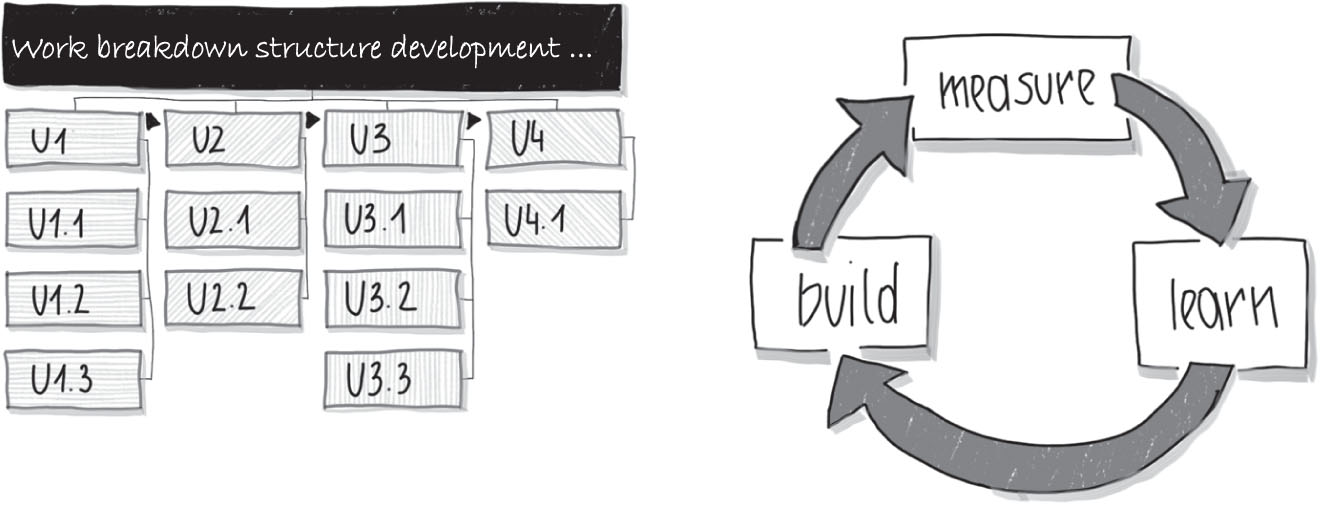

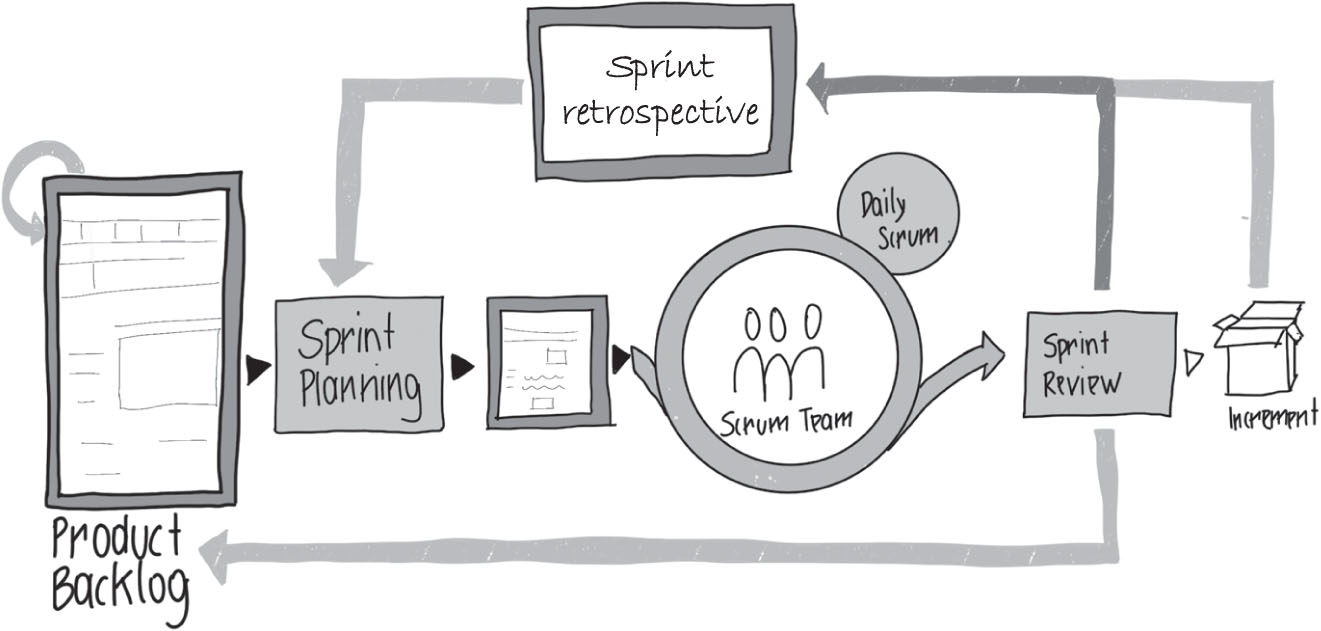

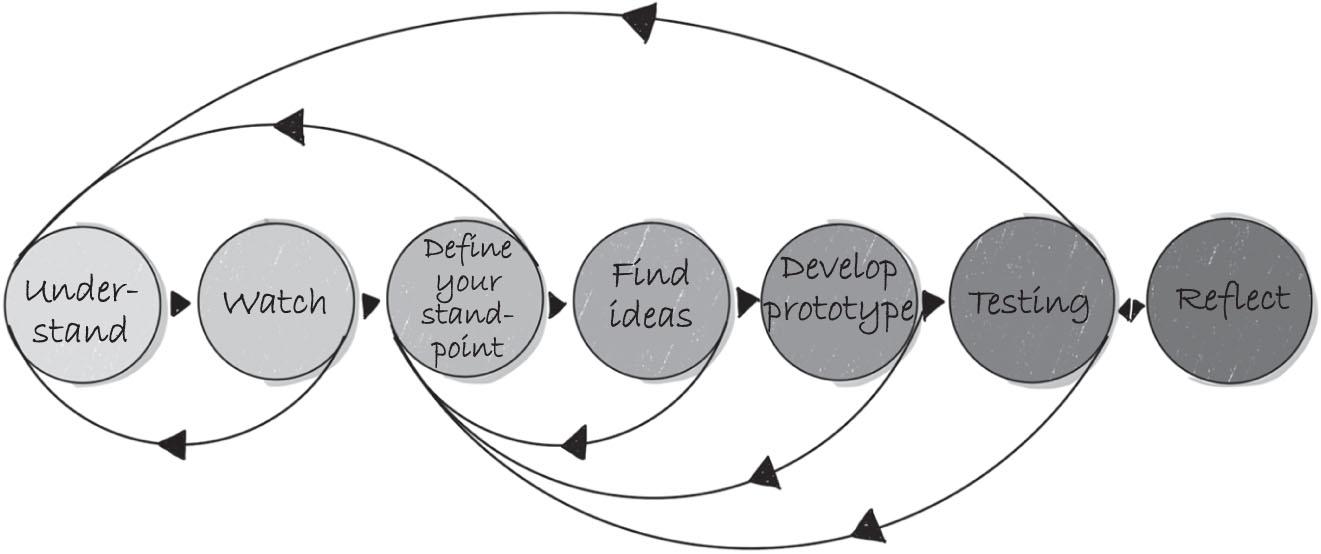

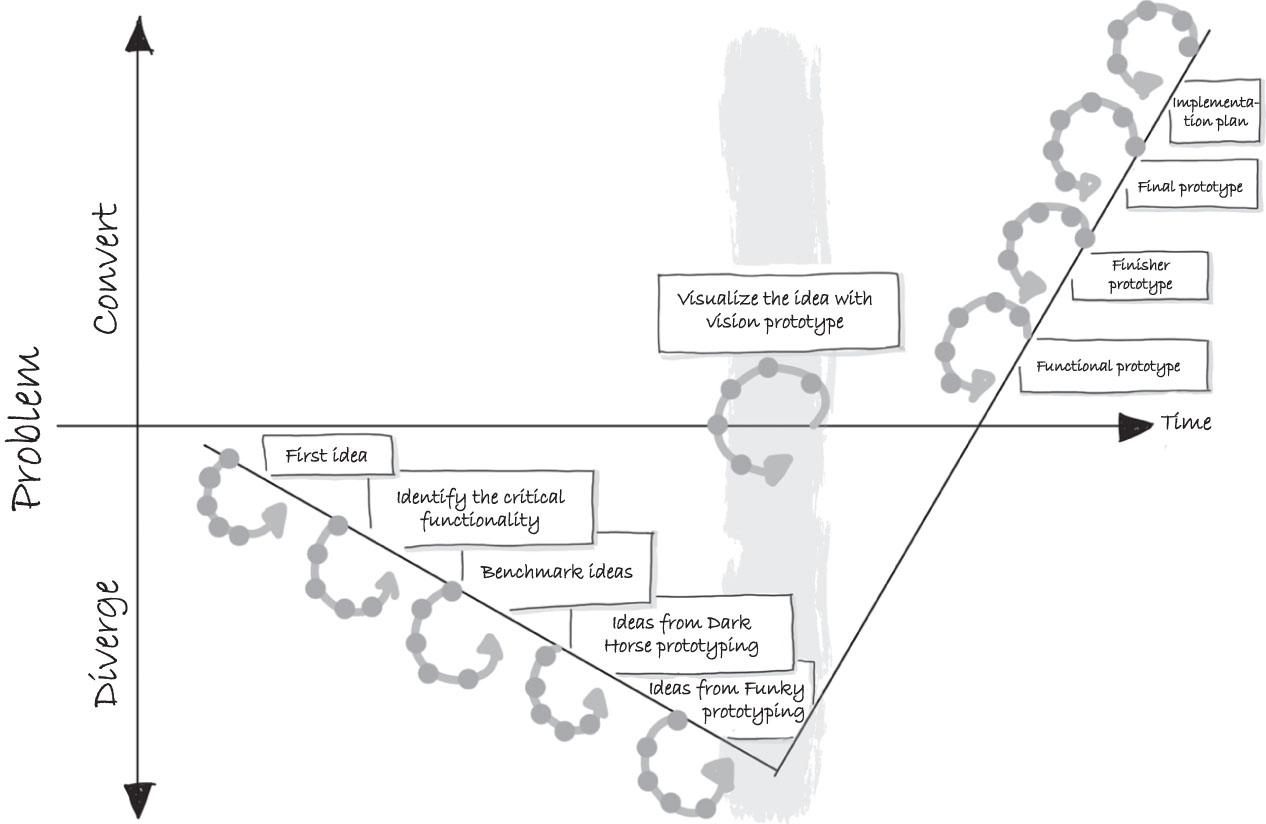

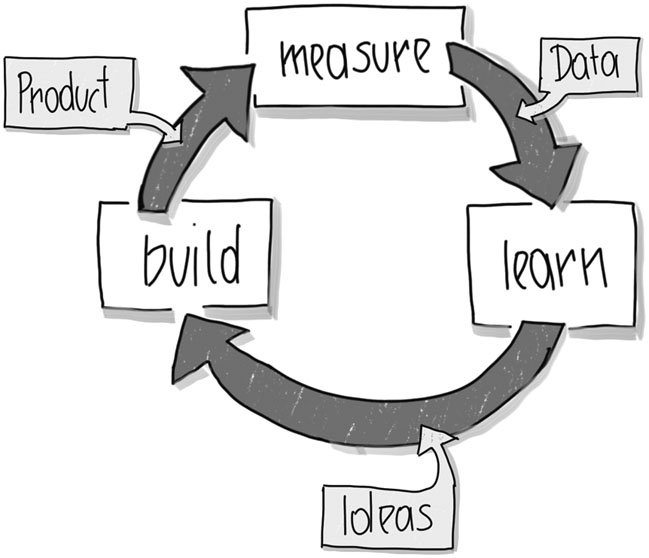

The guiding idea in daily activities is to deal with this uncertainty and unpredictability: Only those who learn permanently stay in the game. This new principle, which is attributed to the startup scene, is build-measure-learn. Three steps in a loop that is run through again and again: Make, measure, learn.

Loops are the model of agile working. Instead of breaking down an issue in detail, as the work breakdown structure in project management does, for example, it is about reviewing and improving the original assumptions (product). This is the essential difference to efficiency-driven logics: It is not the refinement of the product and “plan and control” that are the goal, but the review of the assumptions in the form of “sense and response” that lead to this product.

Fig. 1.2.Work breakdown structure versus build-measure-learn

To start the process of agile working, initially only a small product is needed, a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) . In other words, the product is the answer ←19 | 20→and you try to clarify: Did we ask ourselves the right question? An example: A machine builder who produces electrical appliances, motors and machines comes up with the idea of bringing an electrically powered wheelchair to the market. A project team is established that works according to the basic principle “build-measure-learn”. First, the market in Europe is investigated and the team discovers that insurance companies bear a significant part of the costs of purchasing the wheelchairs. So, in order to develop the market, it is necessary to win them as new customers and distribution partners. The company develops the first prototype of an electronic wheelchair and presents it to the insurers. Unfortunately, these few show interest in the new product.

The project is almost stopped, but the project team wants to learn and stays on. They make an astonishing discovery: A new group of wheelchair users that they had not seen before and recognized as relevant—the active and sporty wheelchair users. The original assumption was that women wheelchair users were people with impairments who needed to be helped and, therefore, needed support from insurers. These wheelchair users were also the insurance company’s clients, which is why the project team adopted this view in its planning. The project team’s new assumption turns the perspective around: What if wheelchair users like to be fit and mobile, do many things for it and do not see themselves as “sick” and dependent on “others”. They might have an active interest in an e-wheely with different features like an integrated smartphone. These potential female customers are more likely to visit shops or online shops that sell, for example, mountain bikes and sports equipment than those that offer health care and nursing products. Under these conditions, completely different sales partners become interesting.←20 | 21→

Thinking in loops has enabled this team to generate new perspectives and bring a successful product to market by having team members work on it step by step. This required the project team to change and work in a completely different way and with different methods. This radical rethinking and questioning is admittedly not easy with a product. Changing the organization to this mode of working is a Herculean task.

And that is what agility as social innovation is all about. However, attempts to transfer these methods, which are suitable for teams and startup companies, one-to-one to entire organizations regularly fail. There is a difference between working on a project with one client, clear focus and prioritization, and aligning the entire organization accordingly. But when a company makes decisions to best serve women wheelchair users, it has a clear focus. If, on the other hand, the company sells electric motors, household appliances, drills and control technology in addition to electric wheelchairs, it has different customers, distribution channels, factories and billing methods. It has to do justice to different logics and is much more complex.

Companies that want to become more agile need organizational relationships that are able to deal with complexity. Agility requires organizational relationships with different starting points. We will show which levers are effective for this. To describe and analyze these organizational relationships, we use the Neuwaldegg triangle (see Chapter 3). The challenging task of shaping the way there, that is, the process of transformation, is what we call agile transformation. This is described in Chapter 4.

1.3.3 Thesis 3: Redistribution of power is one of the biggest hurdles

A prerequisite for agility is that organizations become more open to their environments, that they process impulses from outside, from customers, suppliers, authorities, competitors and their own employees more quickly. But to be consistently open, organizations must give the external-internal relationship top priority. The most important consequence of this change is that the previously dominant top-bottom relationship loses importance. In other words, power relations change; instead of a hierarchical gradation of power, decentralized, distributed spheres of influence emerge in an agile organization (Baecker, 2017). This change in the spheres of power and influence is the biggest hurdle on the way to an agile organization. Many transformations fail because of this.

An example: We were invited by an internationally renowned machine tool manufacturer to introduce an agile organization based on Scrum principles in one area.←21 | 22→

As envisaged in Scrum, there were specific roles: Product Owner, Scrum Master and the team members. In addition, the role of sponsors was established to support the transformation topics. These roles were filled from top to bottom, that is, management level 1 became Sponsor, level 2 Product Owner, level 3 Scrum Master and clerks became team members. So the existing organizational structure was transferred one-to-one to the agile roles. Despite our concerns, we could not persuade the client to change this. Over time, it became apparent that the organization was not becoming more agile and the project was soon discontinued.

This made it clear: Without a redistribution of power, organizations cannot become more agile. The classical hierarchy (from the Greek for “hierarchy”) and the agile organization are not compatible. Hierarchy is based on regulating decision-making powers, that is, power, formally through superordination and subordination. Whoever sits higher up has more rights and more power. This produces bottlenecks, makes people inflexible and in many cases leads to organizations adapting to power relations and no longer ensuring effective processes. Hierarchy as a principle of power distribution has provided stability and predictability, but is becoming increasingly dysfunctional in complex environments.

Power also creates inequality and is seen as a problem in agile organizations. But power structures cannot simply be dissolved. Every organization, every system has and needs a certain distribution of power and would not function without it. Power, loosely based on Max Weber, is the ability “within a social relationship to assert one’s own will even in the face of opposition” (Rudolph, 2017, p. 9). Power has an important function; it serves to reduce complexity and uncertainty. Agile organizations also need this, only here power should be more flexible and widely distributed. The change towards an agile organization, therefore, always means working on the power structure.

The change in power relations often proves to be laborious, as it is often difficult for individual previous holders of power to relinquish their power and thus also lose social significance. But even if those in power are willing and support ←22 | 23→the change, the system, the organization, initially falls into a highly unstable state because complexity and uncertainty increase enormously in the phase of change. The old rules of power no longer apply and the new ones have not yet taken hold: Many things no longer work as usual, everything is shaky and conflict-laden, power struggles break out. Exactly what the existing power structures have so far prevented, namely general insecurity, is now becoming a problem. No system can endure this state of a power vacuum in the long run and therefore many organizations quickly return to the old state.

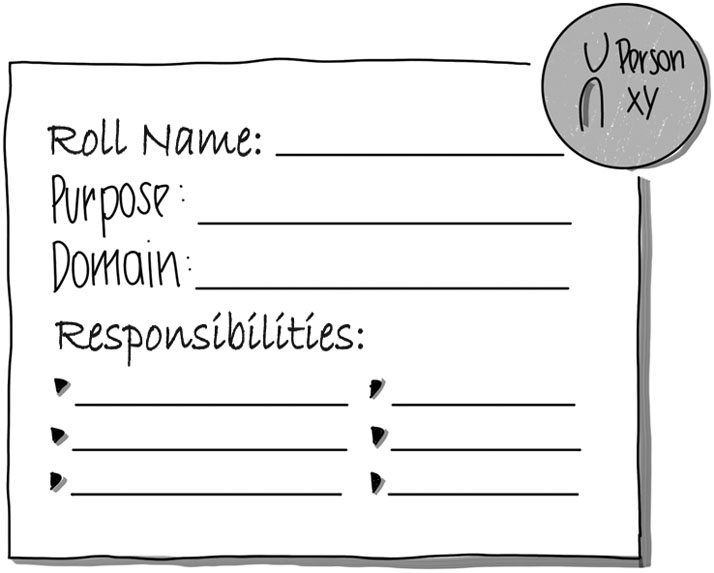

We show how you can work on power relations in Section 3.7 (leadership, power and the transition). Most cases we know of only deal with the issue when conflicts arise. Those who deal with it proactively, on the other hand, focus on transparency and formal role descriptions. They tie power to roles and the powers of what a specific role can and cannot decide on its own, and specify exactly how these powers can be decided. For example, the Holacracy operating system uses a constitution that cannot be changed to determine the rules according to which decisions about the distribution of power can be made (see Section 2.3).

Power can be made visible and limited through rules. Similar to the separation of powers in democratic states, agile organizations rely on transparency and the distribution and formalization of power. But power cannot be completely determined by formal rules, there always remains an informal part. This can be seen, for example, in the assumption of a role: What a person responsible for designing and updating a homepage is allowed to do can be described. What is concretely done and accepted also depends on that person’s experience, competence and willingness to make decisions.

This part of power that cannot be formalized is particularly relevant in the transition. For a further, quite precise description of the powers would not help. The problem, the explosive expansion of insecurity in this phase, remains. But if regulating power does not get the insecurity out of the system, what does? There is only one solution: Trust. Trust, loosely based on Niklas Luhmann, is the willingness to take the risk of assuming a good intention on the part of the other (Luhmann, 2014). Those involved must take the risk and make a leap of faith. Systems that have not learned to build trust will not survive this phase of transition, will dissolve or fall back into the old state of power.

But beware: The issue of power is too difficult to work on a change in the middle of a crisis. What everyone is longing for here is security and no questioning of one’s own leadership. Closing ranks is expected. The fear that power discussions will lead to fragmentation and trench warfare, that the whole system will literally blow up in one’s face, is too great. This is also the reason why the value of popular approval has risen for many government leaders in the Corona ←23 | 24→crisis, even though from the outside some have performed rather poorly. In saying this, we are in no way advocating authoritarian approaches that seek to abuse moments of crisis for their own ends. Our recommendation is:

Work on your power relations in the so-called “normal” times when it may not seem so necessary.

1.3.4 Thesis 4: More and more people want to work differently

For many employees, organizations that are clocked for efficiency and are supposed to function like machines have become stale. This clocking contradicts the natural rhythm of humans and nature, as numerous studies have shown (Moser, 2018). The declining attractiveness of these organizations contrasts with the high appeal—despite poor pay—of the startup scene. The permanently high turnover rates of employees in clocking machines such as the large consultancies are also features of this development.

More and more people want to work differently and develop in the process—agile organizations need exactly that and are responsible for creating this space.

The need to do meaningful work and to be able to develop is growing. This longing for a different kind of organization is met by the book Reinventing Organizations by Frederic Laloux (2016). The book describes concrete alternatives on how to organize and work together differently today. Twelve examples from different sectors encourage meaningful practice. Although at no point is it described what is meant by organization, it meets exactly a need of people who want to shape organizations: The longing to make organizations a better place, a place where people enjoy being, meeting interested others, doing meaningful work and working on relevant issues (for our understanding see thesis 6 and Sections 3.1. and 3.2.).

Today, more than ever, employees come to organizations with this expectation. Work no longer serves the sole purpose of survival, but is also in the service of their own development and should benefit society: They no longer want to be merely a means to the ends of others. They want to experience a practice that focuses on the development of people’s potential. Employees want to be the end themselves. In other words, it is necessary to think differently about the interaction between employees and organizations.

And this “thinking differently” is a particular challenge from our point of view: To open up personal resonance spaces without invading people’s privacy (Rosa, 2019). By this we mean creating a space in organizations where people can open up and reflect on the impact of their actions, that is, share their feelings, irritations and thoughts. This is not about the private lives of staff. This ←24 | 25→distinction is often overlooked. It is not about “bringing your whole self to work”, but about a differentiated examination of the person’s role in the organization. No one wants to have to justify personal relationship problems and an organization would also be completely incapable of acting with such issues of all employees.

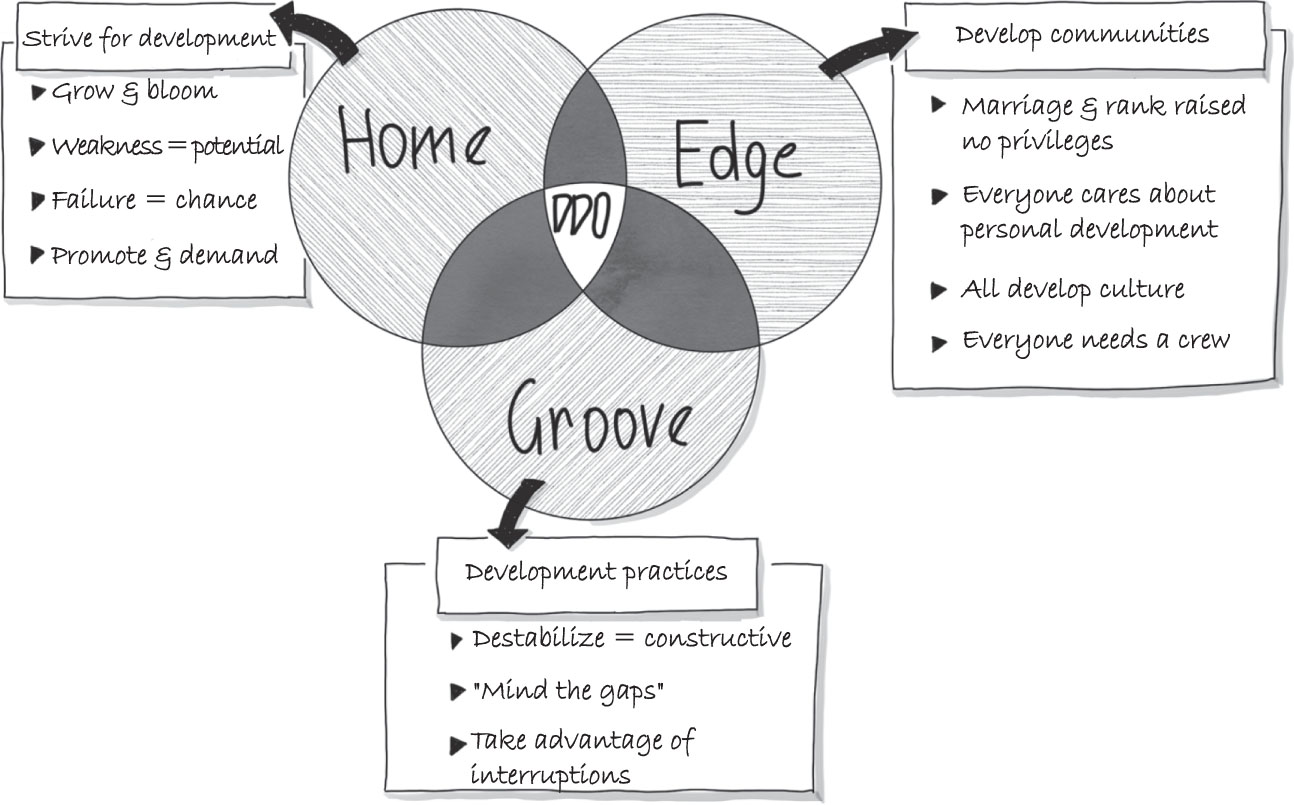

There are already sensible proposals for implementing this requirement, as a variety of concepts and publications on the topic show (Fink & Moeller, 2018; Pink, 2011; Kirchgeorg et al., 2019). One concept that consistently focuses on the development of employees but has not yet received much attention in this country is the Deliberately Developmental Organization (DDO; Kegan & Laskow Lahey, 2016).

A DDO has three dimensions: Home, Edge, Groove—or loosely translated home, edge and practising together. Home encompasses the need to belong to one or more groups that cultivate their own culture and ensure that each develops everyone—all engage in staff development. Edge addresses the need for people to want to grow and develop, where standing still is not an option, weakness is potential and a mistake is an opportunity. This only succeeds when contributors challenge and nurture each other, regardless of their role or status. Groove are the practices of co-development that help destabilize and reflect. So it is not the beat that is the goal, but the discontinuities, irregularities and gaps that need to be overcome and where learning can take place. Concrete procedures are described in the “discontinuous departures”. This does not mean adapting to existing standards, but rather the break, the departure from established routines, in order to consistently dedicate oneself to the growth of the employees and the organization (see Section 3.5).

Fig. 1.3.Dimensions of Deliberately Developmental Organization (DDO) based on Kegan and Laskow Lahey (2016, p. 86)

Today, this and other models are especially effective in places where competition for qualified workers is particularly fierce. You will find examples in Stuttgart, Berlin, Basel, Copenhagen, Barcelona, Vienna and elsewhere. A special place for this has been the Bay Area around San Francisco for years. There, companies like Google, Airbnb, Zappos Future Lab, Patagonia, Morning Star, Berkeley and Stanford University, among others, compete for excellent employees. Competition is fierce and turnover costs money.

The “return of the human being” to the organization is also a consequence of growing complexity. In order for organizations to become more agile, they decentralize tasks and transfer more responsibility to individuals. In classic organizations, there is more or less a “chimney effect” that delegates decisions on unregulated issues almost automatically to upper management. This knowledge that someone is responsible has a security effect in these organizations. In agile organizations, this security has to be established differently, since it can be ←25 | 26→assumed that the experts for certain decisions are not at the top of the organization, but are those who work on the respective front.

Therefore, in agile organizations, individuals are more challenged (see Section 3.6). Figuratively speaking, they have to be constantly playable and cannot easily delegate many decisions. This requires both a different willingness to participate in the organization and new skills to be able to participate. In moving organizations, it is important to combine these requirements with the employees’ need for more meaningful fulfilment in their work (see Section 3.3).

The importance of the relationship between employees and the organization quickly becomes apparent in times of crisis. What is valid now and what can we rely on, the employees ask themselves and observe very closely what the leadership communicates and decides. Small groups form in a flash to compare the statements of different leaders and check their accuracy. Contradictions and lack of transparency quickly make the rounds. The question on everyone’s mind in this situation: Do I still have a place in this organization and how will we be dealt with?

The organization must also be able to rely on its staff, especially in crises. Are the staff able to work and willing to take on their roles? The organization wants to feel that it is important for the staff and vice versa. It needs support, because now ←26 | 27→the staff play a big role. Sometimes, in the exuberance of this energy, the classic organizational structure is suspended: “Hey, we are here and we are all pulling together”. In the process, it “forgets” its processes and roles and thus turns into a herd of startled individuals. This is where resilient organizations prove themselves; they have staff, roles and processes that are attuned to each other (see also Section 3.4).

1.3.5 Thesis 5: Coping with crises is part of day-to-day business

If you remember the Corona pandemic, you probably have images of this crisis in your mind. Like all crises, Corona probably disrupted your usual routines. It was a state of emergency, and to cope with it you needed different means than in everyday life. Uncertainty all around. This is part of the essence of every crisis. It is the state of emergency for which different rules apply than in everyday life.

In this book, we will not deal with the management of acute crises. However, we are concerned with crises here insofar as we analyze those preconditions that make organizations more crisis-resistant. The technical term for this is “resilience”. Resilient organizations manage to cope with an explosion of the unexpected and uncertainty in a crisis.

An organization becomes resilient when it prepares itself in “normal time”. Introducing something completely new only in a crisis seems difficult to us. We recommend that every manager and consultant study crisis research. For example, the classic study by Steven Fink, who investigated the incident at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant in Harrisburg. There, the cooling system in the power plant failed in 1979 and a meltdown was imminent, as happened in Chernobyl in 1986. Fink was an advisor to the newly appointed governor and experienced first-hand how unprofessionally a large traditional company handled the situation despite crisis plans and media professionals. His work is considered the beginning of crisis research (Fink, 2002). This research was followed by many others, such as the classic “The Logic of Failure” (Dörner, 1989), the reading of which can still be warmly recommended today.

A current example of crisis research is the study by the consulting firm McKinsey (Pinner et al., 2020). It shows several similarities between pandemics and climate catastrophes: Crises are systemic, that is, they cannot be confined to individual areas such as the health system, but affect society as a whole. They are not linear, but spread exponentially. They reveal drastic, previously unknown weaknesses in systems, as we experienced with the dependence on important medical products from China. They predominantly affect weak and vulnerable groups of the population, who are even less able to defend themselves against the ←27 | 28→effects than others. And they are not “black swans”—the name given to unpredictable events that change society (Taleb, 2010; 2012). Pandemics and climate change are predictable because experts have been warning about them for a long time.

However, the authors also mention important differences: Pandemics have an immediate effect and pose a direct threat, whereas climate change develops gradually and cumulatively. This difference also explains why there is not nearly the same response to climate change as there is to pandemics.

At the end of their analysis, they summarize: “For companies, we see two priorities. First, seize the moment to decarbonize, in particular by prioritizing the retirement of economically marginal, carbon-intensive assets. Second, take a systematic and through-the-cycle approach to building resilience. Companies have fresh opportunities to make their operations more resilient and more sustainable as they experiment out of necessity” (ibid., p. 5).

McKinsey as well as many other experts assume that crises of all kinds will be upon us. A return to longer phases of stability seems quite unlikely to us, given the complexity and interconnectedness of the economy. So we suspect that coping with crises will be part of the daily business of organizations in the future. Organizations will always have to deal with great uncertainty and they can prepare for it. We want to show you how this can be done with the help of the resilience model (see Chapter 2).

1.3.6 Thesis 6: Organizations are increasingly required to make their contribution to social development (common good)

Organizations are special entities. Like families, couples, tribes and society, they belong to the group of social systems. They exist in many forms, for example, as companies, as non-profit organizations, as associations or as authorities. They differ from other social systems not because of the people, but because of the way they function. They tick differently than a scout camp, political parties or a family. An organization is—from a systemic point of view—a social system characterized by the temporary membership of its participants (employees), its purpose orientation and a usually hierarchical structure (see Sections 3.1. and 3.2.).

Organizations have had a stellar career over the last 150 years. They have changed our society a great deal and have spread worldwide. Organizations have been successful mainly because they have been able to focus entirely on their own logic. Organizations look at the world only from their own perspective, practically ignoring the rest and focusing only on their activities. This indifference relieves organizations and is expressed in the attitude: “I am not responsible ←28 | 29→for the whole world” (Kühl, 2017a, p. 34ff). Unlike a family, which has to take care of all the affairs of its family members, organizations do not feel responsible for much. Organizations are egoists, you could say. They devote themselves entirely to their goals and tasks and learn to pursue them ever more efficiently. It is only because of this relief that the economy and its organizations have been able to develop so dynamically (Luhmann, 1997, p. 724ff).

Since the end of the Second World War, Western societies in particular have demanded that organizations also integrate the interests of others. This led to the protection of workers, environmental regulations, consumer rights and much more. Step by step, these demands were integrated without losing their goal orientation. In this way, the organizations became more and more complex. These demands, significantly called requirements, were and are imposed on the organizations from outside by means of laws. Beyond that, that is, outside the legal framework, organizations can determine their relationship to society themselves; the relationship to society and the contribution to the common good can thus be determined by each organization itself.

This is still true and makes sense. However, we have been observing a change of mindset for some time. For example, organizations that openly display their self-centred attitude have an image problem. For their customers and for their attractiveness as an employer, organizations have to pretend, at least to the outside world, that they are interested in the welfare of others. That is why they donate and make public appearances in charity projects. The phase of exclusive task and efficiency orientation seems to be coming to an end. Organizations, one could say, are being held more accountable and asked about their contribution to the common good. An example of this was the debate on the meaningfulness of state support for airlines after the Corona crisis. What do states like Switzerland, Germany or Austria gain from having a national airline? Wouldn’t it be much more necessary and sensible to invest in the climate-friendly conversion of production, the energy industry and tourism?

According to our thesis, major crises lead to organizations evaluating their contribution to the common good differently and dealing more intensively with their reason for being, their purpose. Why do we exist as an organization? What do we want to contribute to the common good?—“Purpose” is a technical term that we deal with intensively in this book, as it helps us to remain capable of acting in complex situations. Organizations that know why they exist are able to make decisions even in moments of highest crisis. For example, in September 2015, when tens of thousands of refugees flooded in overnight across the Hungarian border, only the Austrian Red Cross was one of the few large organizations able to help immediately. Their purpose “We help people in need” ←29 | 30→mobilized the whole organization across the country without much consultation, clarification of responsibilities and budgets. Over 40 buses were rounded up in 24 hours and brought to the border. The motto was: We know why we are there and what to do. We’ll talk about the rest later.

Organizations that know and use their purpose are more robust and better positioned for times of crisis. But even in normal times, they will be more engaged with their contribution to society, as it is ultimately beneficial for them as well.

1.4 Agile transformation: Why we don’t talk about change management

It is obvious, at the latest after these six hypotheses, that organizational change no longer works in eight steps according to Kotter or according to the classic principle of “unfreeze—change—refreeze” (Lewin, 1963). When so much is uncertain and unclear, how can a simple linear process help? For moving organizations, a classic change management process no longer fits because it does not integrate central elements of change: It is necessary to learn how to actively deal with uncertainty and to permanently evolve in the process. For this, organizations need another form of change: Agile transformation.

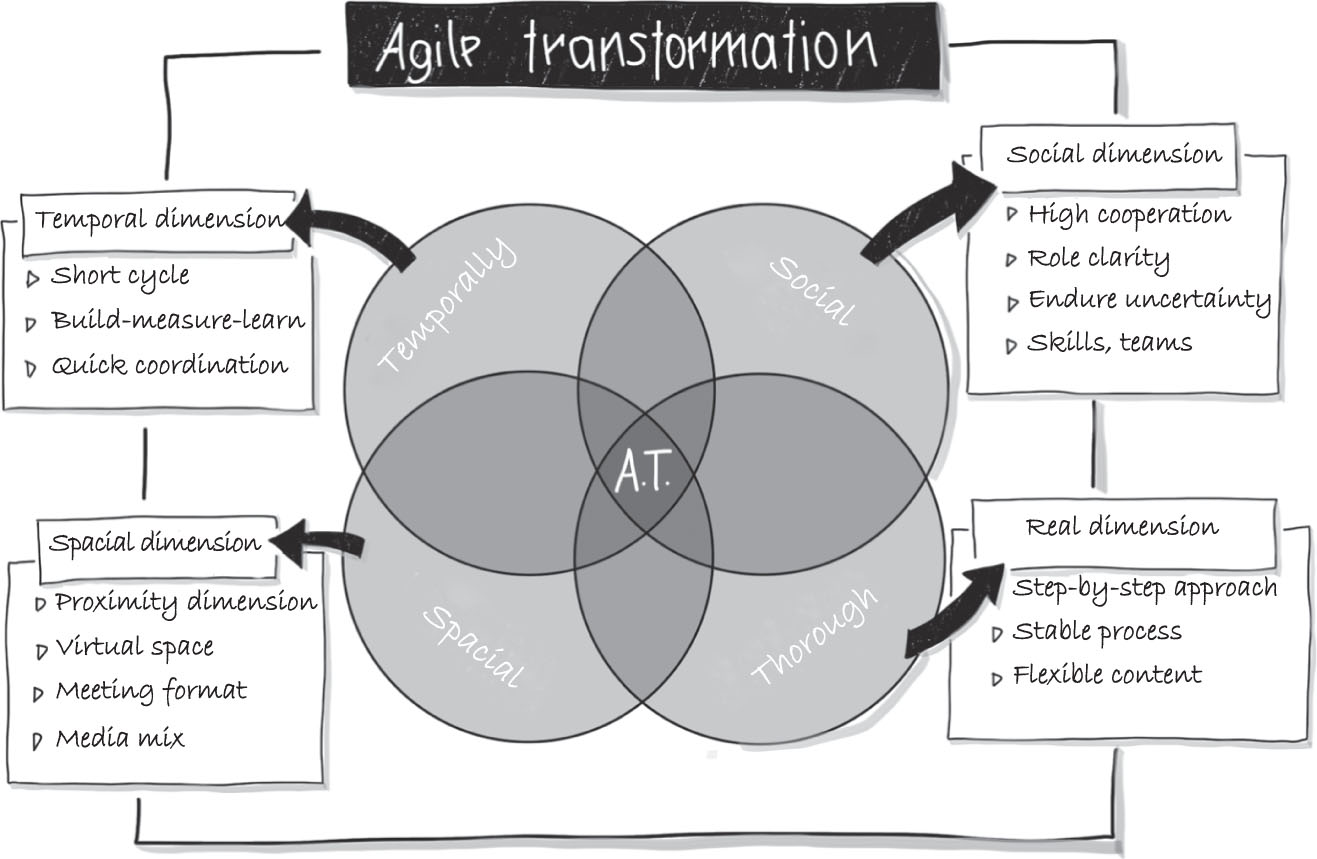

But what changes in concrete terms? As a systemically trained consultant or manager, we always have four dimensions in mind when we accompany transformations in organizations: Factual, social, temporal and spatial (Boos, 2019, p. 46ff). We use the four dimensions to compare classic change management and an agile transformation so that you can see the difference and what the challenge is. Agile transformation is described in more detail in Chapter 4. The most important changes are shown in compact form in Fig. 1.4.

Fig. 1.4.Dimensions of interventions (Boos, 2019, p. 46; Luhmann, 1984)

Time dimension

Shorter cycles are important because things are constantly changing. In the past, planning was done in months, today in days or weeks. The greater uncertainty is met with shorter cycles and each cycle goes through three steps: Build–measure–learn. So in each cycle there is also a fixed step of reflection (learn). The learning relates to how one progresses in terms of content (matter) and how the cooperation runs (social).

Social dimension

On the social level, too, more complexity is expected of the participants. All participants have to endure more uncertainty and insecurity, because the openness of ←30 | 31→the process and the higher transparency are challenging for the individuals. It can only be managed by well-functioning teams. All those who want to actively drive the change process need additional social skills, group dynamic experience and a constant and high readiness to send and receive. In addition, they must be able to handle digital tools competently. This higher density of cooperation is exhausting in the long run. Defining roles helps those involved to cope better.

Factual dimension

On the factual level, the uncertainty is absorbed by the fact that there is a clear process design. For this, rigid process steps are defined that are run through again and again. The process and the roles are rigid so that the content can be flexible. Instead of detailed planning, there is a step-by-step approach, so that the planning only emerges in the course of the process. The necessary orientation does not come from thinking everything through in detail at the beginning, but from a stable process.

Spatial dimension

Spatially, virtual communication and its peculiarities bring a completely new dimension into play for many. We have been used to resolving particularly ←31 | 32→delicate moments in transformation through personal proximity and elaborate spatial arrangements. In a real space, we hypothesize, we have learned to read and deal with social differences. In a virtual space, different rules apply to some extent, differences are coded differently and have to be used differently. Not everything that is possible in real space works in virtual space and vice versa. Therefore, a transfer to a virtual setting is challenging, but also opens up opportunities to learn.

Especially in the last three years, there have been plenty of opportunities for us to learn. Our clients and our projects have made this possible and we are grateful to them for that. The assumptions and models of systems theory have helped us again and again in the agile context and in the crisis and have given us orientation. Some things we have also dropped. So don’t be surprised if we subsequently stop using the term “change management”, because it goes hand in hand with certain assumptions that no longer apply to us. Instead, we speak of transformation. The following case study will give you a first insight.

1.5 Case study: The first three months of ‘I like to move it’

The head of the controlling department of a media company is under great pressure. A difficult workshop is about to take place in the top management circle. Two million euros have to be found for next year’s budget and that gives her a headache. She knows such meetings. When the going gets tough, most managers don’t dare to counter the management, and for some, emotions run high. She decides to bring the Neuwaldegg advisory group on board to work with the management group.

As expected, the workshop is very lively. A wide variety of proposals are put forward: There are heated discussions between management, marketing, controlling and technology. The individuals bring a lot of expertise to the table and work in a highly professional manner. Even though they basically work well together—in the workshop some find the arguments offensive and very difficult. New product ideas are developed, other products are to be cancelled, and it becomes apparent that some proposals are really emotionally sensitive.

Our work as counsellors was to shift attention from the factual to the social dimension. We broke existing patterns of conversation and invited listening and reflection. This led to greater openness in the exchange of assessments.

After two intense days, it is clear to all: “No matter how hard we try, we will not find the two million euros. More of the same will not help us any more.” The situation remains difficult, emotionally stressful and unsatisfactory because there is still no solution in sight. But the leaders are also relieved because there ←32 | 33→is finally clarity about the current status quo of the organization and straight talk has taken place. There is hope in this group that this “new way” of working together will be able to overcome the challenges of the future.

1.5.1 The initial spark

This is the starting point of the agile transformation, later called “I like to move it”. From our point of view, the special thing about this initial spark is the “authenticity” of the moment: No looking away, clarity about the ambiguity, the open insecurity of the individuals and the mutual acceptance of unpleasant things—in a space where the individuals feel safe. And why this title? Because many members of the organization are of the opinion (a vote was taken) that this is exactly what it is all about: Moving together into the future also means that each individual moves. And the best way to do that is to be prepared to do it.

And the willingness is there from many sides and is also backed up by figures, data and facts! It becomes clear that print subscriptions have been decreasing for years and the turnover could only be cushioned by price increases. In addition, the age structure of print subscribers is 60 plus and the publisher has little access to younger target groups. The good news is that digital subscriptions are growing, but not to the extent to make up for the declines in print. The figures are still in the black, but that will change in two to three years, according to calculations.

Internationally, data from other media companies show similar developments. Everyone in the industry is under pressure, many things are unresolved. Therefore, the management team decides to go on a learning journey, visiting media houses and congresses all over Europe. They hope to learn from the radical transformations of others, and they find what they are looking for. Some Scandinavian newspaper houses had dramatic slumps a few years ago, were on the brink of the economic abyss, had to fundamentally reposition themselves and rethink everything. But their first steps after radical transformation seem promising.

The team’s experiences were evaluated and resulted in the following insights for their own company:

• New digital product: The weighting of products will change in the future. Instead of daily newspapers, the focus will be on digital subscriptions. Print will not disappear completely from the market, but its role in the future is unclear, even if it currently brings in the most revenue and guarantees the survival of the company.←33 | 34→

• New business model: It is no longer about free content, but high-quality journalism is in demand, which also has to be paid for. Readers want to be able to distinguish fake news from real news. This requires professional journalists. The advertising market is also changing. Visits no longer count; in the future, high-quality advertising will be placed in a targeted manner.

• Customer at the centre and new, digital way of working: The customer is at the centre by evaluating and processing their data. Journalists use this as a basis for decision-making when writing new articles. It is not only the journalists’ gut feeling and expertise that decide which articles, headlines and word formations work for the readers. Journalists learn daily from the processed data which formats and contents are well received, read and understood.

• Journalistic/social mission versus populism: Digital decision-making bases that are geared to the female reader trigger fears among many that they will increasingly live in an information bubble where only pleasing information is available. There is also a fear of losing the democratic, enlightening mission with which the house has grown up, if only economics counts. A fork in the road has been reached that requires a conscious decision: Do we go in the direction of populism and the mass market or do we continue to feel bound to a social and journalistic mission? The latter means that issues that are important for democracy and enlightenment are still taken up by women journalists. Both paths work and are followed internationally. In this respect, there is an opportunity for the company to strengthen the original roots of journalism by preparing topics for minorities in such a way that they reach a wider audience.

• Personalization: The focus is on the individual. Everyone can decide personally what they want to read about, how and when, and with whom they want to make contact. This corresponds to the current expectations and communication behaviour of female customers.

After so many new insights, it is important for the leadership circle to discuss all of this broadly in order to find a common goal picture and a course of action. Much is comprehensible to the managers, but the assumptions about the approach are as different as they can be. Each speaks from his or her own area of thinking and immediately proposes initial measures: The editorial department, for example, wants a process to set up reports from the departments digitally. The advertising market wants to create a project for new advertising platforms. The reader market is of the opinion that all print subscribers should become digital subscribers as soon as possible. The innovation sector wants to invest in technology first. Many different perspectives that have no common denominator.←34 | 35→

We are familiar with this process. Even though it is clear to everyone that a fundamental change is needed, managers do not yet manage to break away from everyday habits and logics. There is a danger of thinking too quickly in terms of solutions and reproducing the familiar. This is quite normal, and it would be almost strange if it were not so. But it takes patience, a change of working mode in the leadership circle and a viable vision of goals when making such a serious change.

1.5.2 Proven interventions

We like to use two approaches in phases like this: With the systemic loop we collect and observe information to develop hypotheses (see Section 4.2). This broadens the perspective and the leaders can look at what they love in a more differentiated way and also let go. With the Neuwaldegg transformation map (see Section 4.5), the leaders compare their assessment of organizational change competence and motivation. In doing so, we question how the individuals arrive at this assessment and which experiences contribute to it. In the course of the process, the images become sharper for the leadership circle and a common orientation emerges: It is all about transformation! The motto is: Focus on the new and keep an eye on the existing.

The new common ground is the understanding of what is to be done (transformation) and what is to be oriented towards (the purpose, which still needs to be formulated; see 3.3). To realize this kind of new customer-centricity, more agile forms of cooperation are needed. This generates an enormous amount of strength and cohesion in the leadership circle and makes it possible to quickly agree on the next steps together.

Mutual expectations in the leadership circle have risen due to the joint intensive process. But the reality in the transformation workshops is one thing—everyday life is something else! The discrepancy between “the new direction and the new us” and “the current reality” quickly becomes noticeable for the leaders. The temptation to devalue is very high: “Didn’t he understand anything? In the workshop he wanted exactly the opposite!”, “She’ll never learn!”, “It’s just the way it’s always been!” Disappointment spreads and the belief in the transformation sinks quickly.

1.5.3 Three weeks of crisis

Soon the transformation team was in crisis mode every three weeks. Expectations of the leaders are rising. They watch each other at every turn. Sometimes the managing directors decide more in the direction of print and do not promote ←35 | 36→the digital strategy. Sometimes individuals simply cancel entire meetings. After a joint decision, a department head implements something completely different and again and again, up sticks down. Instead of crisis, we as consultants focus on reflection and sample descriptions, and we always keep these four aspects in mind:

1. Understanding does not mean being able to implement.

2. Learning and unlearning takes time.

3. Requiring stamina and frustration tolerance.

4. Positive things are quickly lost, we have to keep looking at what has already been created and developed.

Here, the importance of social innovation in this process of change becomes clear. The leadership circle is in the eye of the transformation hurricane: It is the centre of power, the repository of history and knowledge, home to well-acquired patterns of cooperation and this is where transformation is supposed to come from? Impossible! No one trusts them to do it, not even themselves at first. And yet, they can pull themselves out of the swamp. It is their task to move forward in this process and to carry out the fundamental pattern changes! It’s about new products and forms of communication and collaboration that integrate agile principles. It is about a second order change (see Section 4.5)—for the organization, the leadership circle and also for individuals. We will show you how things have progressed and what we have planned in Section 4.4.1.

2 Crisis-proof through resilience and agility

It was supposed to be a normal meeting day. The team of an international service provider meets every fortnight to pursue and consistently implement the growth strategy that has been introduced. A lot has been invested in the last few months, the team has doubled in size and the last new member has only been with the company for a week. Today they are celebrating their debut. Everyone is still brave at the debut, but at the latest at check-in it becomes clear that nothing will go according to plan today.

Because there is one dominant theme: Corona and the accompanying cancellations by the clients. The team members are uncertain and have countless questions: Is this even a crisis? Do we need scenarios? What is our responsibility towards our clients? How do we deal with it when we ourselves are affected by the disease? What about the orders and the economy? And there is also an unspoken question: What does this mean for the newcomers? What can they rely on? Are they even threatened with dismissal?

A hectic atmosphere spreads. The facilitation team tries to cluster the different questions, looks for responsibilities and possible first steps and answers. It feels gloomy and tough. The meeting itself is not particularly productive, every step is difficult, the view and perspectives seem narrowed. Suddenly someone says: “What if we look at this situation in a completely different way? Namely: We assume that we will all manage it together. What if we do what we do with our clients? Because that’s what we’re really good at.” At that moment, you could have heard a pin drop. This sentence had the effect of a release, the energy and mood began to rise.

Perhaps you have already guessed? This team was us in Neuwaldegg. The crisis has really hit us too. In the very year in which we celebrate our 40th anniversary as the Neuwaldegg Advisory Group, we had to announce short-time work for some employees after this meeting. But this “wake-up call” from one of our members in this meeting has made us capable of acting again and as a result several new products have been created. Projects were pushed forward in spite of the contact freeze. Probably this approach would not achieve this effect with every team. For us, it was the best step at the time and a decisive moment. First, we interrupted a chaotic pattern by referring to our core competencies. Second, it was determined that we would manage the crisis together through short-time work. And third, it made it possible to focus our attention on what we had already worked on, and we could now use that for ourselves. This applies ←37 | 38→to much of what we describe in this book, but first and foremost to the organizational resilience model that we had already been working on for more than a year. It also helped us to cope well with the time of crisis and to remain able to act in the process.

And this is precisely what organizational resilience research is meant to inspire. It shows what organizations do that have come through various crises well, be it wars, financial crises, accidents or market collapses. We would like to look at this in the next chapter and use the findings of resilience research for organizations. You will be amazed at one or two things, because you may be familiar with many of the things that describe resilience from the discussion about agility. We understand agility as all the efforts an organization makes to cope with increased complexity, that is, to remain capable of acting in its environment or, as we say, to remain capable of playing. Agility serves to cope with complexity, and one can measure all methods and proposals by how they contribute to this. Resilience describes the ability of an organization to cope with crises. A resilient organization is robust and crisis-proof.

Agility and resilience, therefore, relate to different contexts—agility to complexity and resilience to crisis management—and thus fulfil different requirements. Of course, these contexts cannot be separated by type, but rather merge into each other, and skills that are useful in one context can also be useful in the other. Nevertheless, the two contexts are not identical. For us, resilience is the more general approach and we see agility as a component of resilience. Therefore, we have chosen a model that helps us to analyze the resilience capacity of organizations It also helps us to capture the rather unspecifically described agile organization in more detail. The proposed resilience model offers a broader and more holistic view of the challenges faced by organizations. Thus, the concept of resilience helps you to make organizations crisis-proof and to classify agility well.

We will take you on the following journey: We start with organizational resilience and will use the Tension Square to identify different focal points for management. For each focus, we will provide you with a grid to help you position your organization and derive suggestions for your practice. We continue with a guide to crisis prevention by training and practising different skills. We then delve into the topic of agility by highlighting the historical development of agile methods for you. These are important in an agile transformation, but by no means sufficient to make an organization agile. That is why we describe agile organizational forms using the Holacracy model. This shows in a compact way what organizations have to work on when they change over to agility. In the penultimate part of this chapter, we show how much the models of agility and ←38 | 39→resilience can benefit from the systemic perspective. The chapter concludes with a client example, a traditional industrial company, where many things were applied, but the process was nevertheless difficult and even had to be abandoned for the time being. Nevertheless, this example helps to understand the principle because it shows how work can be done and what the pitfalls are.

2.1 Resilience: Develop sustainability and become more resilient to crises

At first glance, you probably don’t associate the term “resilience” with organizations. Most people think first of the psychological resilience of individuals: How do individuals deal with difficult situations? How does one recover after a blow of fate? What can be done to protect oneself? Psychology, education and health science have been doing a lot of research on this in recent decades and are always suggesting helpful interventions for individuals.

Originally, the term “resilience” comes from English and means resilience, resistance and elasticity: “When people develop psychologically healthy despite serious stresses or adverse life circumstances, we speak of resilience. This does not mean an innate characteristic, but a variable and context-dependent process. Various long-term studies around the world have identified protective factors that help support resilience to stress” (Fröhlich-Gildhoff & Rönnau-Böse, 2019, p. 9).

Resilience research at the organizational level explores companies that survive and grow despite the most adverse circumstances such as wars, financial crises, resource failure, environmental disasters and accidents. In 2017, the research team around British researcher David Denyer, professor of “Leadership and Organizational Change” at Cranfield University, conducted a meta-study with ←39 | 40→the aim of finding the common thread of resilient organization capabilities and competencies. What is special about this study is that the data basis is based on 40 years of research in a wide range of organizational resilience disciplines: 181 scientific studies, a large number of publications/books and several case studies lead to helpful insights, concepts and food for thought for organizations (Denyer, 2017).

Organizational resilience defines the ability of an organization to anticipate, be prepared for, respond to and adapt to small changes and sudden disruptions—in order to survive, grow through them and even flourish (Denyer, 2017, p. 5). So what distinguishes a resilient organization from one that does not have this capacity:

• A resilient organization can combine several contradictory ways of acting, always with the purpose of surviving and growing and developing.

• It not only reacts, but can also adapt and change in the long term, for example, by adapting processes, developing new products or changing strategies.

• She always has two types of change in mind: The gradual ones that occur step by step and the sudden ones that occur spontaneously.

• The organization is continuously preparing to respond to this, so it is alert to it and finds a common practice for it.

The questions that arise when considering this: How can you determine whether and to what extent your organization is resilient? And where can you start to make it more resilient? Which steps serve to prevent crises and should be implemented during so-called normal operations? Answers to these questions can be found in Denyer’s Tension Square, which we will describe in the next step.

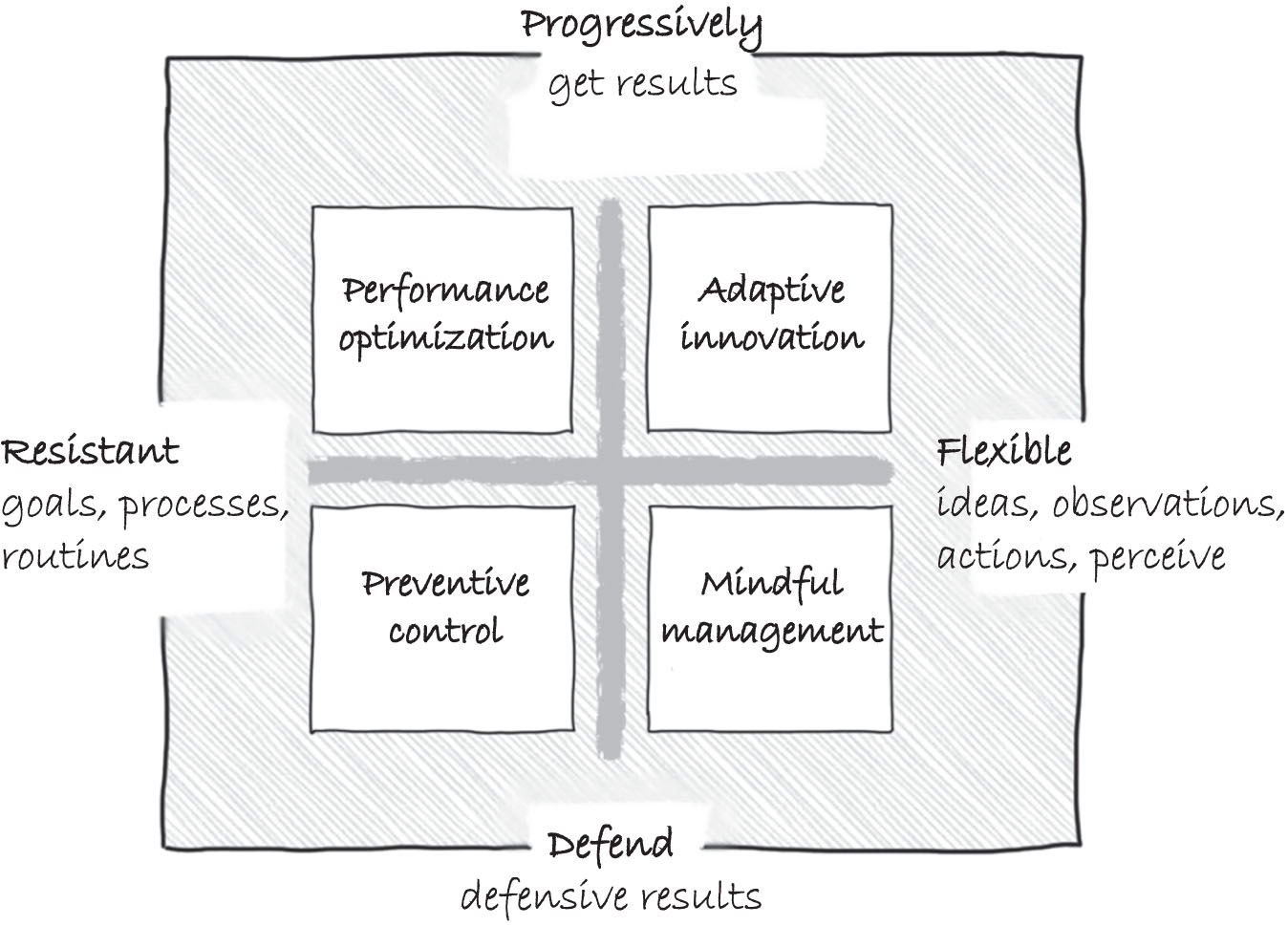

2.1.1 The Tension Square: Protective factors in organizations

The Tension Square works like a map, except that instead of the north-south axis and west-east axis, the poles resistant or flexible and defensive or progressive are used. This results in four fields that describe different capabilities and practices of organizations: Preventive control, performance optimization, mindful management and adaptive innovation (see Figure 2.1). Each field thus has its own focus: Control, performance, mindfulness or innovation.

Fig. 2.1.Tension Square according to Denyer (2017)

Perhaps you have already gained a first impression and examples of the four types have occurred to you. Therefore, we would like to invite you at this point to make a spontaneous assessment: Which focus—or combination of different focuses—is well developed in your organization, team or field, and which field is currently rather underexposed? Example: What we, the Neuwaldegg Advisory ←40 | 41→Group, are good at is adaptive innovation and we are also no strangers to performance optimization. Where we may learn is above all in preventive control. But don’t worry, we won’t stay on this general level, because you will be able to check your initial assessment right away with concrete questions.

But what does this classification mean for resilient organizations? What is surprising about this is that they pursue several focuses and not just one: They use contradictory methods that are both stabilizing and flexibilizing. And they also behave in opposite ways, acting defensively, defending on the one hand, and progressively, forward-looking on the other. Resilient organizations use all these contradictions to their advantage and are not to be found in one focus alone. They do well in all four fields. They are masters in uniting these paradoxes, in managing these differences. This is what makes you so crisis-proof, because it enables you to cope well with complexity (Denyer, 2017, p. 10).

As with resilient individuals, the four dimensions describe protective factors of organizations that ensure survival and growth and thereby promote sustainable development. This approach helps to build a stable substructure in ←41 | 42→organizations that supports organizations in crises and at the same time creates a good framework for agile competences to develop sustainably.

Preventive control

Preventive control integrates defensive behaviour and combines it with stabilizing methods. This makes sense because organizations are expected to be reliable. They establish framework conditions to meet these expectations by setting opening hours, drawing up contracts, offering products on an ongoing basis and paying suppliers on time. For example, if you as a customer buy a car today, you expect the car manufacturer to deliver it on time, make sure it is safe, complies with current legal requirements and that it will still be running the day after tomorrow. To ensure all this, organizations have taken many precautions: Control mechanisms, securing data, certifications, transparently measuring deviations, calculating future developments and problems (Denyer, 2017, p. 11).

A good example of this are organizations with serial production. Order and plannability are emphasized, the focus of management is on quality management and the systematic avoidance of errors. What is loved is what can be standardized. Clear processes and structures are used for control, division of labour and a clear hierarchy are often the result. However, this alone does not make an organization resilient.