Summary

<p>Today, around 80 per cent of activity in companies happens in teams. Yet teams are nowhere near as effective as they could be. The numbers on engagement, productivity, and satisfaction have been clear for years – so how can you build, support, and manage a team that’s high-functioning, effective and successful? <i><b>Building High-Performance Teams</i></b> uses principles from top-class sport to answer this question for the business world.</p>

<p>Full of easy-to-understand and easy-to-implement solutions, and fascinating examples and case studies drawn from the world of sports, <i><b>Building High-Performance Teams</i></b> will help your team to benefit from the authors’ specialist knowledge and personal experience to reach new heights of effectiveness and performance.</p>

<p><i><b>This book...</i></b></p>

<ul>

<li>Helps leaders and organizations to develop well-functioning, high-performing teams for business success.</li>

<li>Uses principles and real-life case studies from high-performance sport that you can apply to the corporate world.</li>

<li>Draws from the authors’ experience in both business and high-level sport.</li>

</ul>

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

Dear readers,

In 17 years as a professional footballer in various countries and now 16 years as a director of the German national football team, I have been able to gather considerable experience and many impressions on the way to success or failure. There are many success factors that determine our path. Every detail counts, but an absolute prerequisite for success is a well-functioning team (on and off the pitch) that pursues a common goal and subordinates itself to that goal.

I love teams. They have been my daily environment since childhood, and I consider the idea of togetherness to be the perfect symbiosis of our human urge to belong and the experience that many tasks in our lives can be solved only in true cooperation.

I am therefore all the more pleased to be able to introduce this valuable book on the inner workings of teams. The contributions of Mario and Stefan, both in terms of content and personality, are also a valuable dynamic, as they illuminate the process of team development from two different perspectives: psychological and data-based analysis, as well as practical experience from the world’s top sports teams.

With this, the authors capture the pulse of the times exactly. In an increasingly data-driven world, we make purposeful use of modern technologies and draw valuable information from them for the further development of our systems. From my own experience, I can tell you that the information that scouts and video analysts in modern football can generate in a very short time about players, teams and tactics no longer has much in common with the days of my active career 30 years ago. Opponents are virtually transparent and numerous evaluations and studies can be used to prepare the next strategic steps.

At the same time, in a highly technical world, it is still necessary to look at what is decisive: the people involved. The necessary qualities in social interaction become all the more important the more I allow myself to be guided, and sometimes distracted, by data and external information flows. People will continue to be at the centre of our interaction, especially when it comes to developing and leading real teams. Analytics and performance indicators are the perfect complement to a strong human component in leading teams. I particularly appreciate the emphasis on this symbiosis in this book.

I’m sure many of you have already felt and witnessed the emotional power and impact that can come from real teams. I will never forget the feelings and memories of our 2014 World Cup title in Brazil. This success was a prime example of long-term detailed planning, in which we paid attention to every little detail beforehand, no matter how tiny it seemed. However, the grandiose success in Rio’s Maracanã Stadium was only completed by the great performance of “the team” itself, which was perfectly tuned by the coaching team and emotionally accompanied by a peak performance. The dedication, mutual support and permanent belief in success made this team something special in the tournament. A real high-performance team!

It is therefore worthwhile to invest concrete thoughts, good preparation and personal energy in leading people. If I do this in a sincere, goal-oriented and appreciative way, I get back more than I have given myself.

This book provides you with valuable, scientific input, creative food for thought and practical advice on how to lead your very own high-performance team and experience successful moments together. Make the most of your time. Leadership is a privilege. And achieving great things together with others is clearly more of a calling than a profession.

So this is a book about teams. So far, so good. But what for? We are firmly convinced that well-functioning teamwork makes two important contributions to the world of work, now more than ever.

On the one hand, in our society of opportunity, teamwork offers an important social counterbalance to increasing individualization. More doors than ever are open to individuals to shape their personal life and work path. And this is precisely where, in our observation, teams in particular continue to provide the necessary support, as well as orientation and joy, in doing things together.

On the other hand, teams are an operational-organizational answer to a working world that is becoming ever faster and more complex. It requires organizations to adapt flexibly to ever new challenges and to make qualitatively better and faster decisions in order to enable entrepreneurial success in the future.

Building and leading a high-performing team is therefore a core task of every manager. At the same time, it seems to be the greatest challenge to understand exactly what it takes and means to develop such a team sustainably and stably. In the following chapters, you will learn how you can succeed on the basis of the latest findings from top-class sport and team science.

The corporate world likes to look a lot at competitive sports and sometimes envies the coach for the joy and euphoria that the emotionally charged team members radiate. So, the question is: how do managers achieve an equally outstanding team performance in everyday business life? This is exactly the challenging question we have been asking ourselves for many years. In this book, we would like to present our findings to you. From our experience, there are congruent principles in competitive sport and the corporate world that increase the likelihood of long-term success along this path.

We, Mario and Stefan, have been fascinated and passionate about professional teams for many years.

Mario studied economics with a focus on organizational psychology and then worked for a specialized management consultancy for several years. Even then, his focus was on organizational design and team effectiveness, before he finally co-founded his first HR tech company in 2012, which focused on communication between managers and employees. Before the majority of the company was sold to a leading German insurance company, it had around 45 employees. Since the beginning of 2018, Mario has dedicated himself to building up the team architecture specialist MONDAY.ROCKS as Managing Director. At the time of publication, this technology and consulting company has ten employees and serves around 35 SMEs, as well as corporations in the German-speaking regions of Europe. In recent years, Mario has been involved in the analysis and development of more than 120 teams in this role.

Stefan is originally a fully qualified lawyer, but as a long-standing co- and head coach of the German men’s national hockey team, as well as a Bundesliga coach and player, he primarily brings his outstanding experience and success in top-level sports to this book. Including the two Olympic victories in 2008 and 2012, he is distinguished by 12 years of practical experience that have had a lasting impact on his view of the development of high-performance teams. In addition to his sporting successes, Stefan has been active for many years as a keynote speaker and, since April of this year, in the development of organizations with his skills-training “TrainYourBusiness”. In doing so, he inspires teams of well-known companies through the same amazing parallels that are also considered in this book. It is precisely this interplay between everyday business life and the playing field, between employee interviews and nomination interviews, between board meetings and trainer meetings, that has been and continues to be the reason we both enjoy comparing, developing and discussing so much. We hope that you, dear reader, enjoy it as much as we do!

The world of work continues to change at an impressive pace, bringing with it ever new standards for collaboration. Just think of all the changes around New Work. Agile working methods such as Scrum, Kanban or Design Thinking are just a few examples. Here, teams are automatically at the centre. Also, and especially for them, it is increasingly about adapting to new requirements and making collaboration more flexible and effective.

In public discussion, teams, especially “teams at the top”, are the measure of all things. The principle of shared leadership is gaining ground, think for example of the dual leadership of the Social Democratic Party of Germany and the Greens, or in the SAP leadership. Even though the “experiment” involving Jennifer Morgan and Christian Klein at SAP was broken off after only six months, it will certainly not have been the last attempt by a major German company to share competences and responsibilities at the top. In the following, we want to explore together why this is so. After all, there are extremely successful models, such as that of the three Samwer brothers, who as a three-person management team created market giants like Zalando with their company “Rocket Internet” and left the competition far behind. The awarding of Nobel Prizes has also shown a clear trend in recent years: it is increasingly research teams that receive the coveted award.

Top-level sport has been leading this development for many years; coaching teams at eye level are now considered standard. In the early 2000s, the Swedish dual leadership around Lagerbäck and Söderström paved the way for a principle that is now also lived practice in the German national football team. Experts like Joachim Löw and Oliver Bierhoff act independently in their respective areas of expertise, yet in the best possible way. Despite all the emotionality with the ups and downs of the last few years, no disagreements leaked out. Oliver Bierhoff and Joachim Löw exemplify a principle that is becoming more and more prevalent: today, head coaches establish entire coaching teams around them, and the time of the autocrat is over (almost) everywhere.

We have already mentioned being a big fan of rules of the game. They provide a framework that allows for orderly coexistence. Within this framework, there is a free space, a playground for creativity. Our book works in a similar way: we give you a professional framework, a structure within which you can move freely. Take this book as a companion that inspires you as soon as you need it.

You will see that we have always combined insights from science with practice and our own experiences. The personal touch, which is important to us, has always been balanced with the view of leading science, sometimes also in long discussions between us authors and long-time companions.

We did not aspire to write a “one-size-fits-all book”. That would not really be wise either, as there is no standard for dealing with people. Contexts determine the respective situation and prohibit a simple copy-and-paste of tools or instruments.

Rather, our aim is to point out central success factors, in the periphery of which there is valuable potential for successful team leadership. We have summarized these factors at the end of the book in our Team Force Seven model. We are convinced that addressing these seven pillars is the foundation of successful teamwork. Depending on the size of the team and the working environment, you will certainly encounter other aspects and it will then require a corresponding focus. However, you will (hopefully) understand with this book why it makes sense to approach our model, or even parts of it, again and again. Because team development does not end, it is an ongoing process.

Concrete tips support you in developing approaches for prompt implementation in your working environment in as condensed a form as possible. Our three expert interviews also give you an insight into real-life practice.

In the course of this book, you will encounter terminology that we use to make our ideas more vivid and understandable. By the way, this also applies to another target group of this book: your staff. This principle of a common, simple language that everyone can understand can be wonderfully transferred to top-level sports. It’s about simplifying complex game analyses and analyses of the opponent, making them comprehensible for everyone and operationalizable for decisions made in seconds.

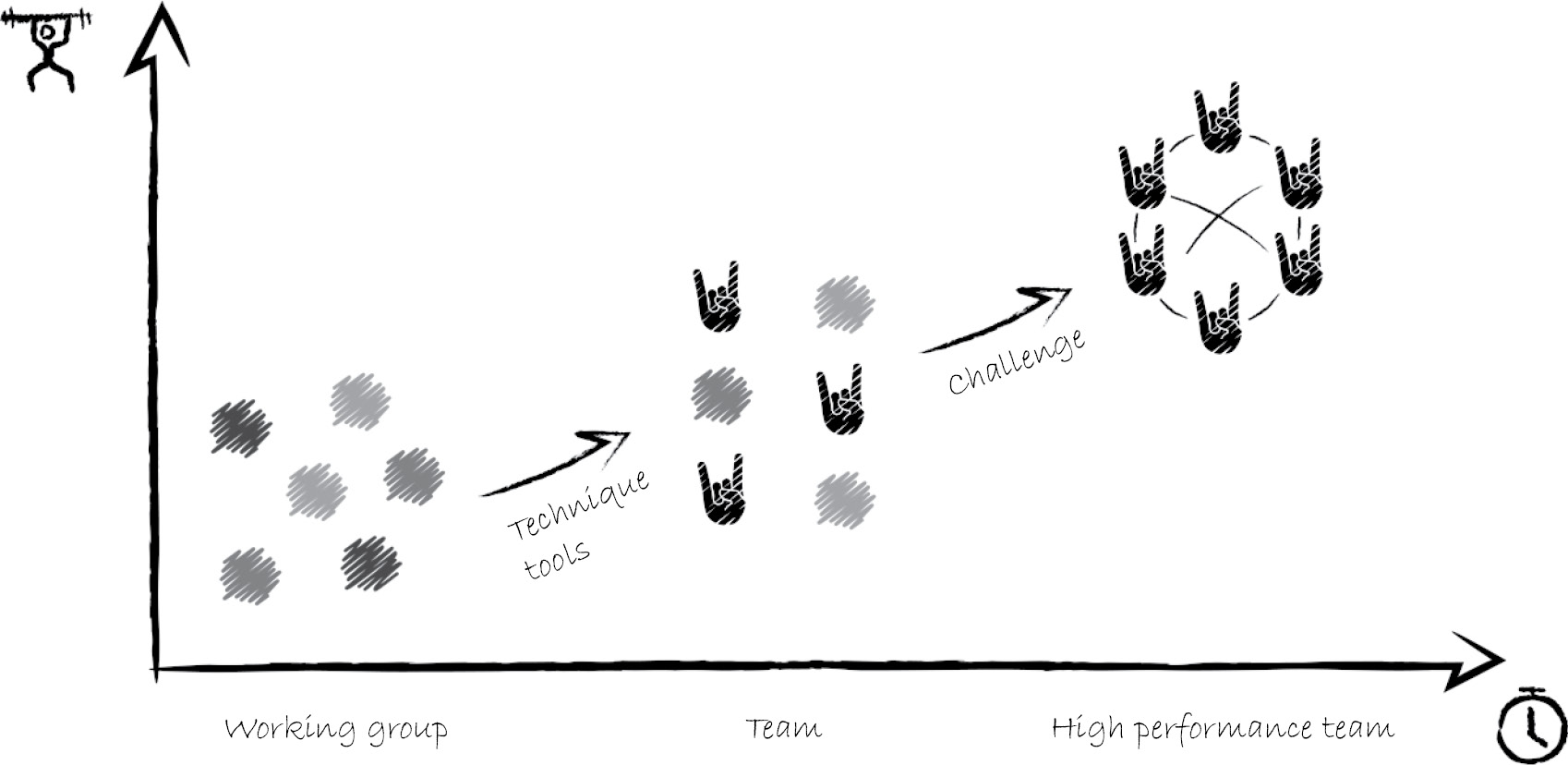

We speak of three forms of human cooperation: the group, the team and the high-performance team. Ultimately, we are in the goal of developing a performing unit in practice from a group that has been put together on paper. In this book, we describe how this can work and what needs to be considered in the development towards high performance.

In our context, recognizing high performance means always taking a double look: at the qualitative inner life of a team and at the result. You will read that we see an important connection here and advise every manager to look primarily at the performance factors of a team and not only at the desired result. Correspondingly, positive results will be the consequence. High performance is therefore achieved by those who deliver above-average performance over a long period of time and repeatedly push the limits of what is possible. High performance is therefore a standard for the way we work together and approach every form of challenge in a new and targeted way again and again. It also means being robust against external disturbances, as the inner workings of the team are so stable and well-rehearsed that disturbances ultimately actually move it forward instead of paralyzing it.

The structure of the book is based on our Team Force Seven model. So, let’s take a journey together through the central factors of team architecture. And let’s always keep in mind: team development is not linear, but a dynamic process.

The common thread is the constant look at the worlds of competitive sport with its spillovers and parallels into everyday business life. We enter the playing field of team architecture with a focus on the individual team member and their inner drivers to be part of a group and a larger, common goal. Only if we really understand teams and their members do we have the chance to set the right impulses for sustainable team development in leadership.

We show you where the decisive impulses lie on the way to a real high-performance team and what an important role the leader plays. Of course, the following always applies: without high-performance leaders, no high-performance teams can be created.

Enough of the preliminaries. Let’s dive into the exciting world of team architecture!

There are people who get up on Mondays and actually go to work full of passion. What kind of people are they? Where do you find them? And is this behaviour, which is rather unusual for a Monday morning, due to the corporate culture, the behaviour of the managers or the good pay?

Modern team science today assumes that ultimately none of the factors mentioned is decisive for perceived happiness and satisfaction in the team. Rather, we humans seem to be concerned with how well our personal values and interests are reflected within and in the environment of our team. If you have already been through several career stages, we would now like to recommend the “fall height test”. And it goes quite simply like this:

!

The drop height test

Take a moment to think back and recall the perceived emotional drop from Sunday to Monday at different stages of your professional career. What do you notice?

If you’re like most of us, the drop-off point is much lower in a team that shares your personal values, and where your individual perspectives are valued, than in a team where they are not. This is because shared values and a sense of being in the right place almost always lead to something we call personal commitment. So, one key to team success is to decipher what really drives your staff. Because based on this insight, you can tackle exactly the problem that—according to studies as well as your own painful experience in team leadership—has been prevalent (worldwide) for years: commitment in teams. Imagine the human and business levers you could use to create a high-performance team if you, as a leader, could get to grips with this challenge.

That is exactly why this chapter was created. We want to support you in making your team feel both understood and in the right place. To achieve this, we will show you the exciting parallels of personal commitment between competitive sport and business teams that would otherwise have remained hidden from you. Let’s get started!

1.1 Why we do not feel success

Mount Everest in May 1978: almost exactly 25 years after the first ascent of the 8848-metre mountain, Reinhold Messner becomes the first climber to reach the “world’s peak” without artificial oxygen. A sensation that doctors and other experts had previously considered impossible. Later, however, Messner will report that none of the (happy) feelings he had expected from this moment occurred. All he felt in the heights of the Himalayas was a deep, inner emptiness and only one wish: to return to the valley.

Monza, near Milan, 10 September 2000: Michael Schumacher wins the Formula 1 Italian Grand Prix and, with his 41st victory, finally catches up with his great role model Ayrton Senna. When Schumacher is asked about this at the subsequent press conference, he is speechless. He lowers his eyes, hides his face under his cap and bursts into tears. Twice, he starts again and tries to answer the journalists, but he doesn’t manage it.

What happened in both cases? According to their own statements, both exceptional athletes realized that they had reached the peak of their careers at that very moment, and that the feelings and sensations they had imagined did not arise.

Let’s take the example of Kevin-Prince Boateng. A polarizing professional footballer who has played in the best leagues in the world and has reached financial heights that are probably closed to most of us. Excitingly, he revealed in an interview that he once bought three expensive luxury cars in one day when he was under contract with Tottenham Hotspur in London. But what moved him to do so? During an interview with the Italian newspaper La Repubblica, he explained:

I didn’t play and wasn’t even in the squad. I was looking for happiness in material things. A car makes you happy for a week. So, I just bought three to be happy for three weeks. Unfortunately, I learned that it doesn’t quite work that way.

Of course, we already knew before Boateng that money alone does not make you happy and thus cannot be the real meaning of work, or does it? Because some of us seem to see it quite differently. Otherwise, how can we explain the astonishing number of people who, with an 80-hour week and little social life, work solely towards their yellow Porsche 911 Turbo? There are still too many people who want to find their work motivation through money or—as in the case of Schumacher and Messner—reaching a supposed career peak. Unfortunately, this leads to the fact that we live in a society where most people are clearly not doing what makes them feel permanently in their element.

Our point of view: most people—and thus of course most teams—lose a great deal of potential by focusing on something in the area of personal orientation that does not trigger any real personal commitment in them. For this reason, it is particularly important to us to place the individual perspective and meaningfulness of work at the beginning of our joint journey.

1.2 What does your path look like?

Beijing, Olympic Games 2008: the exceptional swimmer Michael Phelps competes in eight races, wins eight gold medals and thus becomes the most successful Olympian in history. What a dominance. On the internet we find numerous videos of his daily training routine. The footage of the Olympic pool, in which he swims his lanes incessantly, day after day, is striking. He has followed this rhythm since he was diagnosed with attention deficit disorder at the age of seven. A daily routine that involves an incredible amount of discipline. But a daily routine that helped and still helps him to lead a happy, balanced life. A path that seems to be made for him.

Do you think he would have kept up the first years of intensive training if he had only been interested in the eight medals in Beijing? No, back then, the Olympics didn’t have the significance they have today. Swimming was pure passion. The fun of success certainly gave him the last percentage to win later, but the main motivation was his enthusiasm for the sport itself.

!

Short break: Self-reflection

What does your path look like? Can you express the why (not the goals!) in one sentence, towards which you align everything?

Yes, we know common answers like “to be successful” or “to become financially independent”. The problem is that we only talk about the result, the final state, like reaching the summit of Mount Everest or catching up with your idol at Monza.

The way success is predominantly defined, it can never make us happy. Why? Because for us, the decisive reward lies exclusively in the last, final moment. This burden is simply too high if there is no joy along the way!

Often, we can better recognize the meaning of a word via other languages. For example, the English word success is much closer to the German term sukzessiv and thus to the meaning of the path to something. So, it should matter less to us where we want to go, but rather how the way there shapes and feels to us.

!

We hold

Success is the state that arises when you follow a path that suits you.

Results—detached from the actual joy of doing—cannot and must not be the sole reason for acting. Understanding this not only helps us personally and saves us from emotional disappointment. It also makes us better leaders and entrepreneurs because we understand how commitment can arise in our teams. It thus brings us a first step closer to successfully building high-performance teams!

In a study in the USA, managers were empowered to offer their female employees anything they wanted. Any function, any task was possible if they could communicate it clearly in ten minutes. Well over 80 per cent of the female employees surveyed failed at this opportunity. They could not clearly name what they needed to be really happy in their job. And that is a paradox, because at the same time most of us strive for professional self-fulfilment. And your co-workers, consciously or unconsciously, also expect you to express yourself clearly. Other studies show that even with a longer period of reflection we don’t come to a conclusion, and two-thirds of adults don’t know what they want professionally. And therefore, they don’t know how to get there.

Where does this insecurity come from? As children, we adopt many views, values and role models from our family, our teachers, our friends or society in general. Adopting such perspectives at a young age makes a lot of sense—purely in terms of evolutionary biology—because we learn by copying behaviour. Unfortunately, these perspectives later have little to do with ourselves and our own needs. We follow the principle: “We don’t even know what we want, but we always want what we know.” Ultimately, in this way we fall far short of our actual potential for performance and happiness. The personal search for meaning is therefore worthwhile. In other words: Correctly align the compass of your employees before you send them on their journey. Only then will they arrive!

We could contemplate this thought and its meaning intensively for a long time. Many philosophers have already done this before us. For you as a leader or entrepreneur, however, one thing is crucial: if you want to develop high-performance teams, you must start with the individual team members and their individual paths. Because the personal orientation of each individual determines the success of your team. And how do you achieve this in professional practice? We will show you four models, the first three of which provide the mental framework, while psychometrics, an applied branch of psychology, finally enables you to put them into practice.

1.3 Aristotle’s eudaimonia: Good actions

Aristotle was one of the great Greek philosophers, eponym of the famous Google team study “Project Aristotle” for more team effectiveness and actually one of the first to deal with the topic of engagement. His thinking was highly influential both in his time and later. From his study of humanity emerged an ethic in which the concept of eudaimonia, which is interesting for high-performance teams, also plays a fundamental role.

The first thing Aristotle describes about the conceptual model of eudaimonia is that each of us has one and the same purpose. And that is to achieve your eudaimonia: a state of calm and lasting contentment and not just a momentary heightening of the senses, such as via the focus on results already described.

In this way, our actions are evaluated as good or bad, depending on a goal. Thus, when we perform a certain work, this action is good if it gives us satisfaction and bad if it does not. Consequently, according to Aristotle, a good path for us is one that contains as many of these good actions as possible.

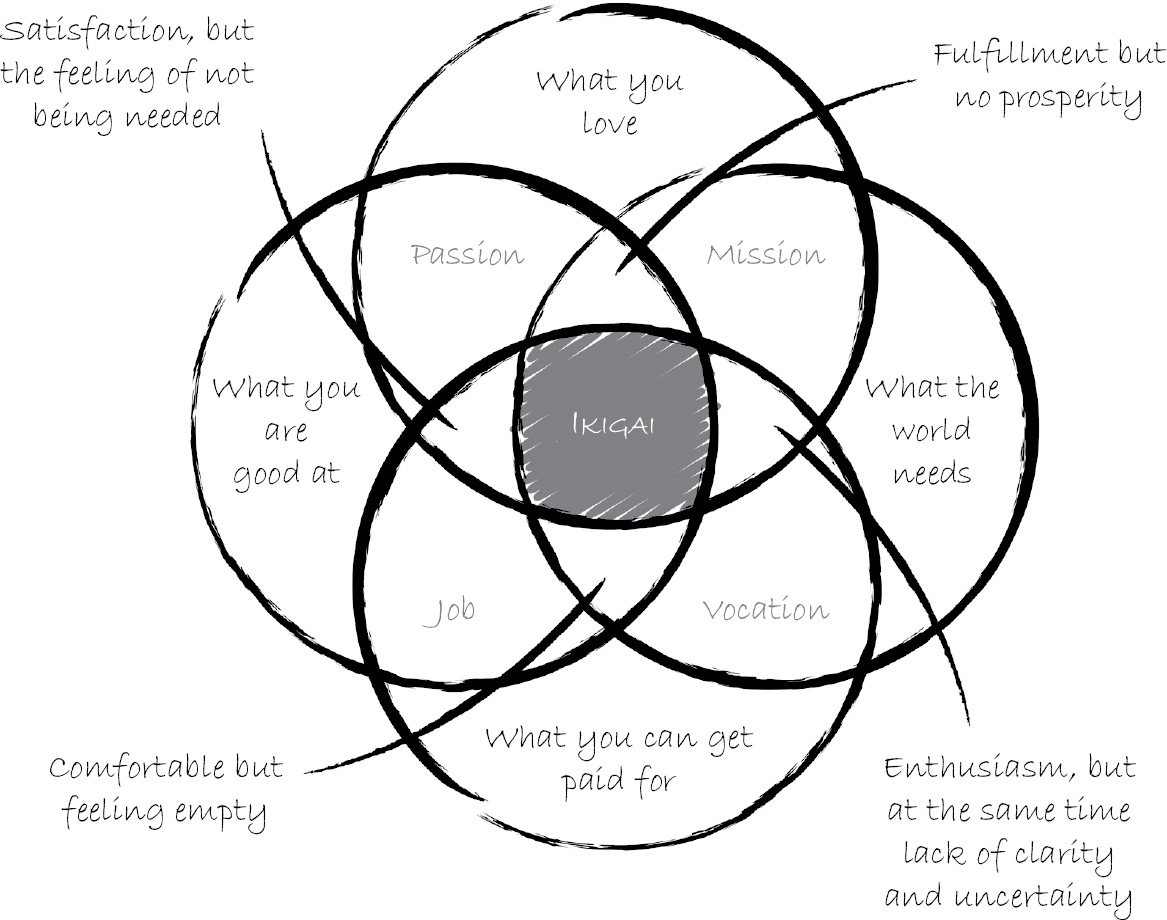

1.4 The Japanese Ikigai: Find your meaning

Japanese culture has also been dealing with the question of the meaning of work for centuries and also has a term for it: Ikigai. It is made up of the words iki (= life) and gai (= value, effect, usefulness). Translated linguistically, it means “your reason for getting out of bed in the morning.” Ikigai is effectively the “place” where your passion, mission, calling and career intersect. And at the same time, it describes the path you should find for yourself and your employees in order to optimally exploit job satisfaction and performance. In our language, we then talk about meaning. In the Ikigai model, this is illustrated by the overlapping circles of the diagram. The point where the circles meet is the place where you find your Ikigai: your path, or also: your personal sense of work!

1.5 Simon Sinek: Start with why

The famous video of the TED Talk “Start with Why” by Simon Sinek now counts well over six million views on YouTube and has set an incredible movement in motion. This video about the Golden Circle clearly shows why people are happier when they find meaning in their work. And meaning is most likely to be found by those who can also achieve something (subjectively) meaningful with their own work. That is undoubtedly true. But the question you have to ask yourself as a manager in everyday life is: what does this mean for each individual employee? And does each employee already know their why? The answers to this question are complex, because meaning is highly individual and depends on the values, passions and perspectives of your employees.

Yet it reads so easily: “If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up people to collect wood and don’t assign them tasks, but teach them to long for the endless expanse of the sea”, formulated the French writer Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, who also wrote The Little Prince. Of course, this example remains true, but it only shows part of the whole. In fact, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s sentence describes the overarching framework of action of a team in an organization. Every company exists for a reason and pursues a certain vision. What the sentence does not pick up on is that every employee also has their own personal why. By focusing on the individual why of each staff member, you can discover together their personal role in the team. The following should apply: the individual’s attitude aims to be the best person for the team, not the best person in the team.

It is therefore a matter of each team member contributing their individual possibilities for the improvement of the team in such a way that they experience their own actions as an important contribution and that this is perceived as equally appreciative by the entire team.

1.6 Psychometrics: Value structure and interest inventory

Of course, psychology, or more precisely psychometrics, also deals with these questions and speaks of meaning structures, which are decisively based on the measurement of psychometric value and interest inventories. The exciting thing: the findings obtained in this way make it possible to decipher individual paths, especially in a team context. They create a kind of compass for the individual meaning of your work—and, of course, that of your colleagues.

!

Practical tip

Measuring psychometric inventories is a decisive practical step towards the high-performance team.

Value inventory

Values are a central element in our actions. They describe what is of particular importance to each individual and they are closely linked to our personal journey and our why.

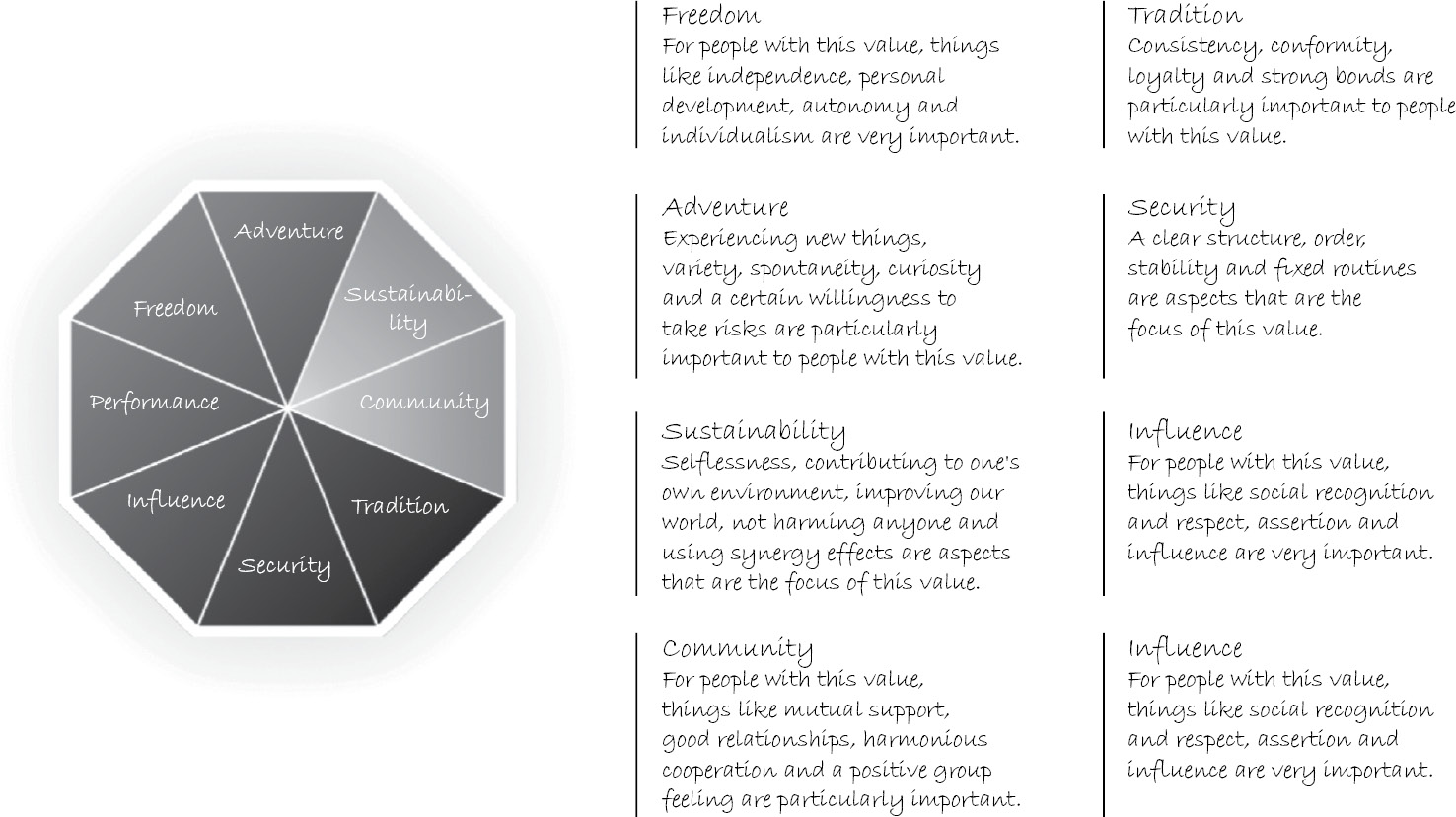

The survey of values in psychometrics is largely based on the value model developed by Shalom Schwartz in the early 1990s. He distinguishes between eight types of values that can be arranged in a model.

The closer the values are to each other in the model, the more similar they are. The further apart they are, the more opposite they are.

Interest inventory

Another approach in psychometrics to approach a person’s individual path to a personal sense of meaning in the work context is the interest structure inventory. It decodes what you particularly like to do, for example, in contrast to other team members. This interest inventory is your potential, which you bring into the team individually.

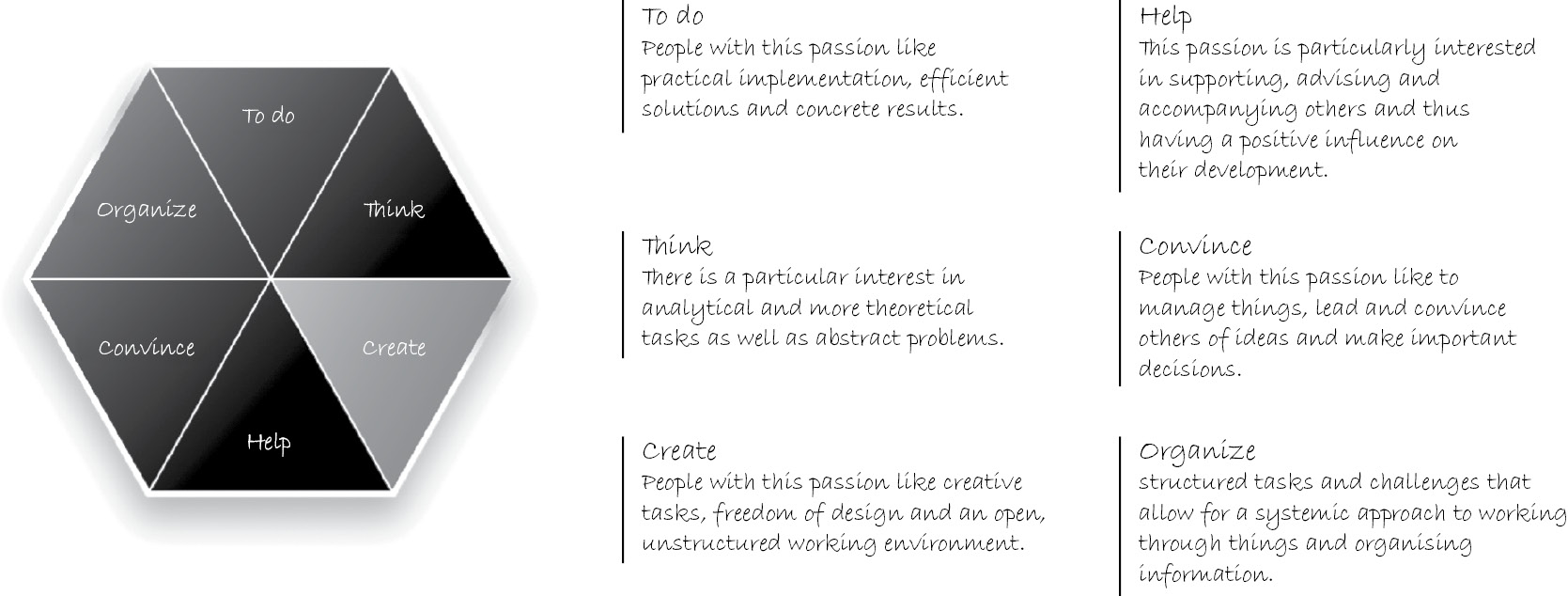

The survey of interest structures or interests is based on the hexagonal structural model of occupational interests by John L. Holland, which was already developed at the beginning of the 1960s. Since then, it has been continuously developed further and is therefore considered empirically valid. Six types are postulated on the basis of which people can be distinguished.

The closer the types are to each other in the hexagon, the more similar they are. Opposite types are most dissimilar.

It is the combination of both psychometric inventories in their modern interpretation that makes them particularly valuable for understanding individuals and thus also for orienting people in the work context. In the words of Arthur Schopenhauer: “In the same environment, everyone lives in a different world!”

1.7 From personal commitment to the role in the team

Now we know that personal orientation is a first, decisive criterion for satisfied and high-performing employees. And these employees form the basis for high-performance teams. So, another challenge is for them to be able to bring this sense of work into their work environment. Studies show that it is primarily the (approximately 20 to 30) people in our immediate environment who decide whether we experience our actions as meaningful. This puts the team and the task of the individual in the team at the centre of considerations.

Employee engagement is not synonymous with job satisfaction, nor does it simply mean job enjoyment. We can be satisfied with our job and still not be engaged. For example, there are people who find their job okay, but only live out their true passions after work. This is what we like to call a leisure-oriented attitude.

!

We hold

All engaged staff are happy, but not all happy staff are engaged!

The difference between engagement and satisfaction lies in performance. Engagement is therefore also the degree to which an employee is personally and actively involved in the success of the company. Engaged people go out of their way to perform well because they feel a strong emotional connection to their position, their team and the perspectives they share. They want their company to succeed because they identify with the mission, purpose and values of what they do together on a personal level. We then call all of this the sense.

Why is this so important? A 2017 study by Deloitte indicates that low engagement leads to a loss of productivity of one month per year per employee. In addition, the overall productivity of a team is also reduced by up to 21 per cent. Add to this the cost of employee turnover and we arrive at a factor that can account for up to 34 per cent of total staff costs. A classic lose-lose situation, because at the same time, commitment is also a question of personal happiness and health. The AOK Absenteeism Report 2018 came to a clear conclusion: “Meaningless work makes you sick.” Companies with above-average employee engagement, on the other hand, outperform the key figures of their competitors by an average of 122 (!) per cent, as Accenture Strategy was able to prove.

!

Short break: Self-reflection

What is particularly important to me in the work context and in dealing with my colleagues? And what perspectives do I bring to my team?

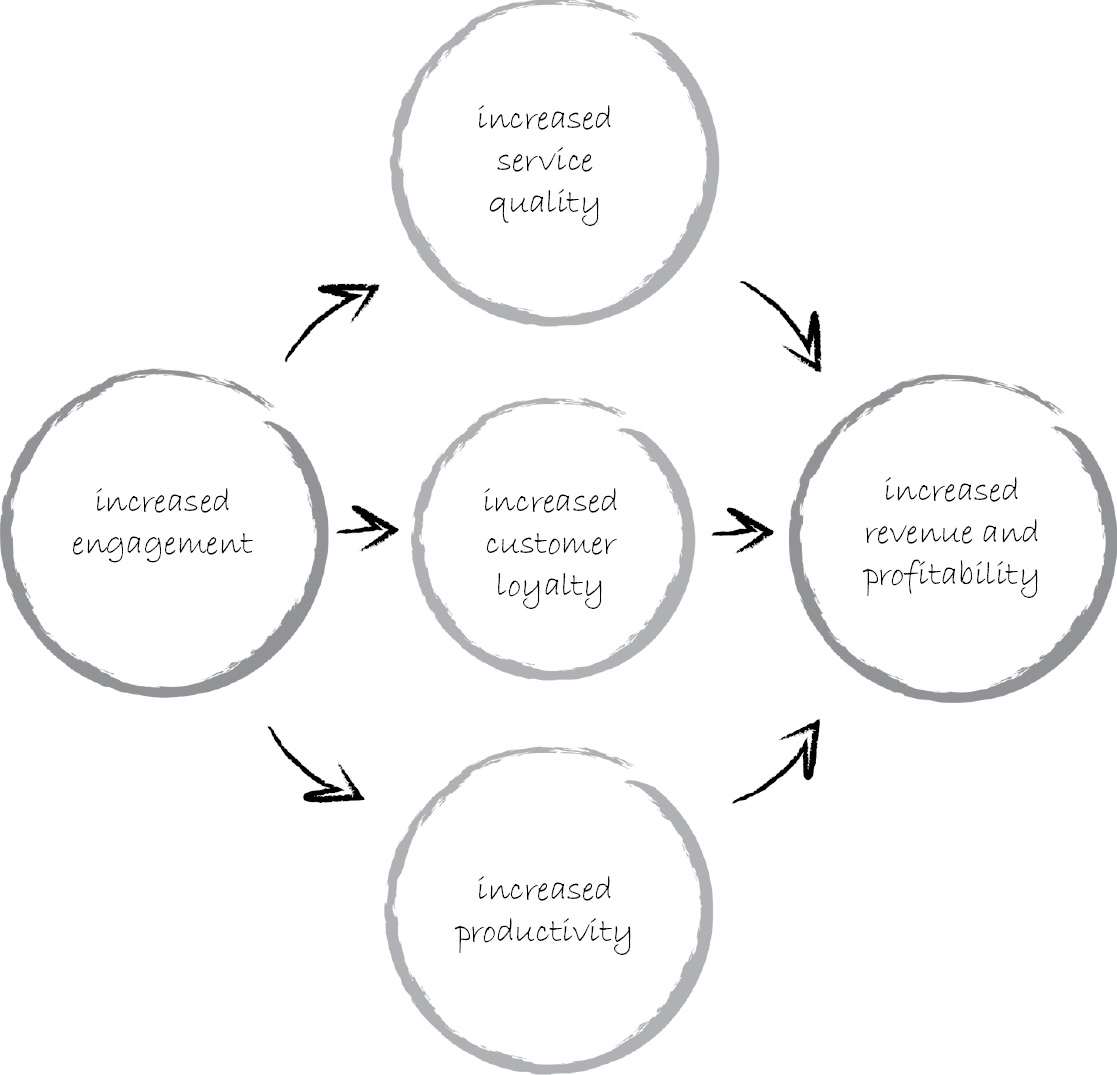

The impact of personal commitment on your team results is well reflected in the service profit chain model, a model first developed by Harvard Business School researchers in the late 1990s and popularized by the book of the same name.

The service profit chain model attributes profitability to the value of satisfied, loyal and productive employees. Companies must create the conditions for satisfied and engaged employees to create valuable, loyalty-inspiring experiences for their customers, which in turn increase profits.

Good leaders know that engaged employees drive innovation, enhance team performance, increase productivity, grow the business, improve customer service and foster loyalty both internally and externally.

Studies also show that companies with above-average employee engagement consistently outperform their competitors in profit, productivity and turnover. In other words, you cannot afford to ignore the (lack of) engagement of your employees.

We summarize

Understanding why each person in your team does exactly what they do is a crucial step to becoming a high-performance team. Deciphering what drives your employees and where their sense of purpose lies is the basis for performance and satisfaction. If the joy of the experiences on the way to the goal prevails in your team, and the team does not only concentrate on arriving, then you are doing it right. High-performance teams need employees who know themselves and can optimally bring this knowledge to the team. So, the most successful teams and teams in the world literally have fun playing the game. We take with us the fact that:

happy employees are more interested in the experience than the result.

After starting with a view of the individual, we are now slowly but surely expanding our field of vision to the whole team. A team can be assessed from an external observer role, which is possible for everyone. What kind of tone is there? Do the steps of cooperation really go hand in hand? Do all team members wear the same work clothes or are there differences in their external appearance? All these questions, and there are certainly many more, initially only assess an outwardly perceptible appearance. This appearance reflects something that arises deep inside a group as a collection of social beings—we call them people. So, to understand why teams behave this way or that, it is worth taking a deep look inside. This is where the true drivers of their motivation and the hindering causes of their underperformance lie, in equal measure. An elementary driver of whether teams (want to) appear like one to the outside world is the common goal and objective. What sounds banal at first glance is sometimes a highly complex matter. And this is because in a group of people, at first completely understandably, there are particular interests that need to be developed in the same direction in the sense of team development. Only when this unity of purpose within a team is paired with the will to achieve the best possible performance can we speak of teams that are capable of great things. So, let’s take a close look at the diversity of goals and why it is so important to deal with them on a permanent basis.

Boom! What initially sounds as if it could be a colourful sticker slogan is actually a small Belgian community just outside Antwerp. It is Sunday, 25 August 2013. The German men’s national hockey team become European champions after a 3–1 victory over the Belgian hosts. As with the German women’s final victory over England the day before, the match was high-class and exciting right to the end. Bright sunshine and a stadium full of 8,000 mainly Belgian fans did the rest. It was the third major success for this team in a row, following the European Championship title in 2011 and the Olympic victory in 2012. The rise of this hockey generation began with the Olympic victory in Beijing in 2008.

It was the deserved and consistent success of probably the best team in the world at the time. At the same time, the tournament taught us a lot about team dynamics and coaching. So, if you’re wondering what there is still to improve after a European Championship title, we can clearly answer from our own experience: quite a few things!

To put it in perspective: the boys’ final performance was outstanding and the victory more than deserved. For the final victory, the central defensive line had to be changed because two important players were absent due to injury. What appeared to be difficult and new in terms of personnel was solved by the boys in a great, flexible and self-confident way. The leading players knew how to categorize external influences, and disruptions were perfectly ignored in the spirit of a high-performance team. The desire to succeed and, above all, to enjoy all the emotional moments were their great motivational drivers, as the boys reported again and again, even years later.

What finally ended so successfully and was celebrated in a highly emotional and team-typical manner until late at night, started anything but promisingly a week earlier. What looked to outsiders as if it had been planned long in advance felt anything but the result of great preparation on the ground. We are in no way concerned with disparaging this title. In competitive sport, it is still true that “whoever ends up on top has done a hell of a lot right and also deserved to win.” We are more concerned with a realistic assessment and the ability not to evaluate successes and failures in an undifferentiated way. It is about learning to understand how they came about. After failures, we tend to rush to data to analyze exactly why something didn’t work out and what can be done better tomorrow. With successes, we usually see the result somewhat naively as the logical consequence of our great work and avoid looking at what didn’t go so well too. We have to reflect on how much of our own performance, how much luck and how much help from the competition played a role in the outcome of the event.

!

We hold

Always critically examine the causes of failure and success afterwards.

Back to the tournament in Boom: it got off to a bumpy start and the team didn’t really get rolling. After an opening defeat against Belgium, Spain was the next opponent. At half-time, Germany was trailing 1–2, and a defeat would have meant missing out on the semi-finals and any medal dreams. With a tremendously energetic performance, the boys turned the game around in the second half and scored five goals. The last group game against the underdogs, the Czech Republic, resembled a “stranglehold” despite the victory, as the coaching team made unmistakably clear. In the semi-finals, the strong neighbours from the Netherlands were waiting.

The feeling that something was wrong continued to creep through the corridors of the team hotel and through the joint appointments between the players and the support team (staff). At some point the decisive sentence was uttered: “No wonder things are going so bumpy, we came here without a clear goal.” Boom, that really hit home. Now it was clear to everyone: take a deep breath and think. Did we really not have a clear goal? Was it not clear to the team what they wanted to achieve in this tournament?

The result of the internal ad hoc analysis was unfortunately (or fortunately): “Yes, we arrived without a clear route, a common story or clear performance goals.” The question now was how this could be corrected as quickly as possible and whether this was even feasible in an ongoing tournament. Before addressing this challenge, it is worth taking a look at the equally important question of how this could have happened. After all, the team was still led by Markus Weise, Germany’s most successful hockey coach, who won a total of three Olympic gold medals with both the women’s and men’s national teams (2004, 2008 and 2012).

It is important to know that, at least in hockey, the post-Olympic years, and 2013 was one such year, are always years of reorientation and rejuvenation of the teams. Established players end their careers, young talents join them. Coaches develop innovative playing systems and principles for the challenges ahead.

In any case, the German men’s team could be described as successful or even spoilt for success in the summer of 2013, after all, they won gold at the Olympic Games in 2008 and 2012. The main goal in 2013, to qualify for the World Championships in the following year, 2014, had already been achieved by the time of the European Championships described above. So, what came next? This question was considered self-critically and not really answered in advance. To help resolve the story and, above all, its cause, let’s take a closer look at the topic of goals and their manifestations.

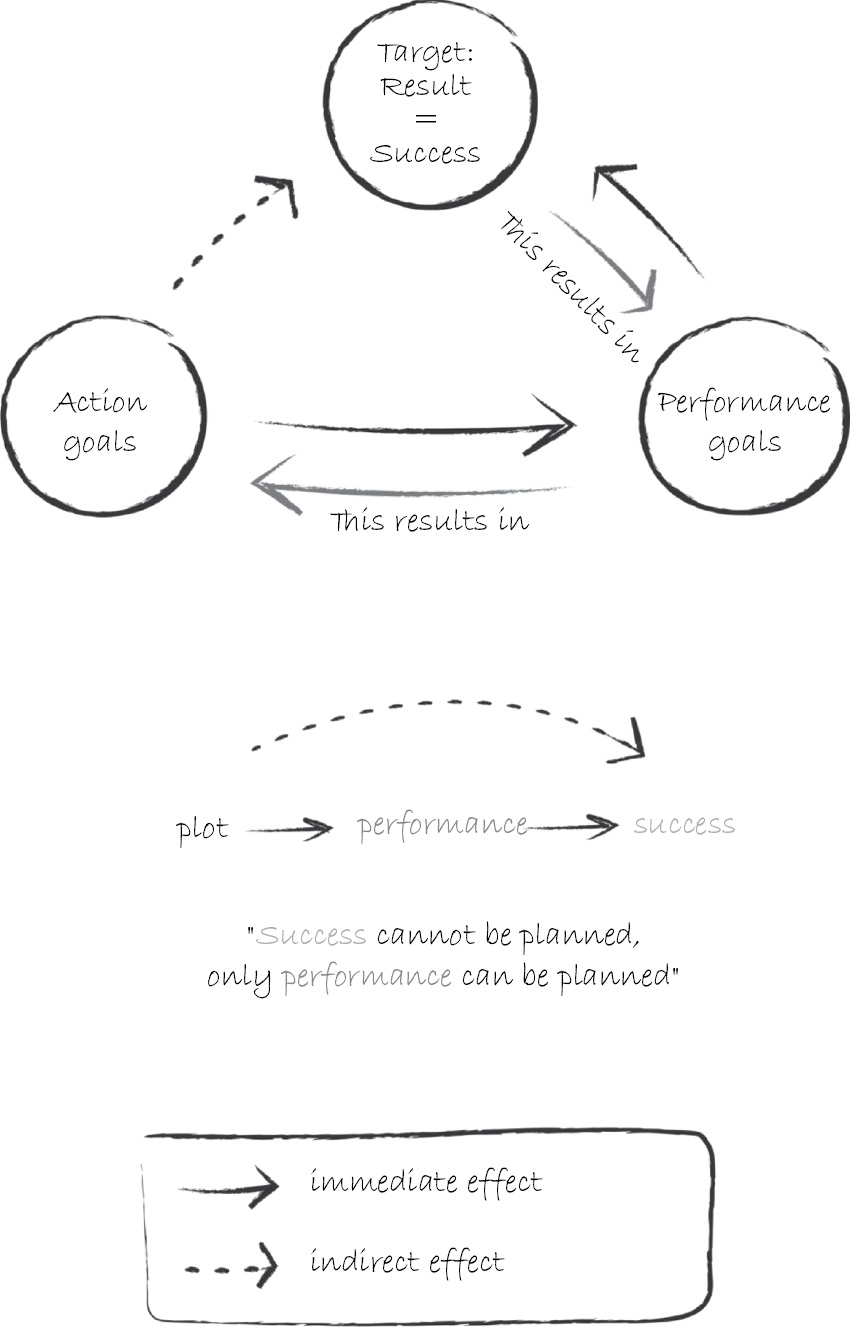

Here is a short, important digression: it is about understanding how success actually comes about. Numerous guidebooks convey the belief that success can be forged with a tool if the instructions are only written clearly enough. What sounds seductive is 95 per cent not applicable to our sporting and entrepreneurial environment.

Success on the drawing board works, if at all, with clearly schematic processes that are purely about process optimization and causal if-then solutions. If I have direct influence on the entire value chain of my performance, external influences tend towards zero and I have the monetary means to create the preconditions quantitatively as well, only then can I think about success in terms of the paint-by-numbers principle. Otherwise not.

!

We hold

Success cannot be planned, but performance can. (unknown)

The only thing that seems to be plannable to some extent is personal performance. In dynamic times and complex socio-economic ramifications, we are more convinced of this than ever. You can directly control this performance through actions resulting from action goals.

You are holding this book on team architecture in your hands and now you read that success cannot be planned? Then what is the point of all this? It is true that even success planned down to the last detail is not 100 per cent certain. But with this book we make it more likely! With methods, tools and personal deductions, we want to increase your chance of taking your team to the next level. The more knowledge is combined with experience, the more likely success will be. We should therefore have the confidence to see ourselves as architects of our teams. Because if we don’t take on this role, the hoped-for outcome is beyond our control and becomes very unlikely.

This basic understanding is not only important for further reading of the book. It is, in our opinion, the basis for recognizing how effort and output actually fit together. Where and how do I have to provide input in order to be able to think about outcome at all? What sounds banal is not so simple. In Chapter 7, we deal more intensively with the question of controllability and our own effectiveness in dynamic environments. For we are not only concerned with understanding a model of thinking, because that would be too simple and theoretical. Rather, it is about the fundamental decision of my positioning in the environment that drives me as well as the ability to recognize through which of my actions I can and want to make a difference.

!

We hold

Results, at best successes, come about through achievements and these in turn through actions.

In the following, we consider three types of goals in this context:

−Performance targets (outcome targets): they form the starting point of every objective and describe the type, time and form of target achievement.

−Action goals: they describe the concrete, individual action of the individuals.

−Performance targets: they continuously define certain intermediate results, resulting from our actions on the way to the overall performance target.

2.2 Goals for success: The what for

Performance targets, also called outcome targets, are clearly quantifiable results that at the same time define the what for. These include match results, league placings, measured times, title wins, etc. Performance targets have the advantage that it is possible to check exactly whether a certain result has been achieved or not. As is well known, results do not lie. We have already pointed out the importance of analyzing causes independently of results.

Developing goals for success, alone or together with a team, always makes sense when we want to move ahead towards a specific event and achieve a certain result at the end. This result, which is evaluated as a success by everyone, represents something like the North Star in the sky, which gives me orientation and direction: “If I know what I’m working towards, it’s easier to slave away.” Surely, you have already experienced this personally in one way or another. We are convinced that the clear answer to the question “Why all this?” has to be at the beginning of every goal-setting process. We must answer why it is worthwhile to make a certain effort. We can do this in a spontaneous conversation with a colleague, in a—hopefully meaningful—meeting and finally also in the context of a major event planned long beforehand to initiate possible transformation processes with staff participation.

Without a clear goal or at least a specific intention as to why a conversation or meeting seems to make sense at this particular time, I waste valuable time and energy. And this has a direct impact on the further course of the project. “Begin with the end in mind”, proclaimed management mastermind Steven Covey in his world bestseller The 7 Ways to Effectiveness back in 1989. In short: if I don’t know where I want to go, I don’t even start running. For the romantics and conscious decelerators among us: this does not mean a relaxed walk on the beach or a city trip, where consciously letting go is liberating for body and soul and personally necessary relaxation is right and important. We are primarily concerned with working together with intrinsically motivated people and creating a common basis about why and for what we should henceforth make a joint effort. So, if we seriously pursue the goal of developing a team that is clearly better than the average, a clear concern must be worked out.

At this point we refer to our expert interview (all about heart, head and dream teams) with Prof. Dr Gerald Hüther, probably Germany’s best-known brain researcher, following this chapter.

2.3 Goals for action: The what

Action goals describe what must ultimately be done to achieve a certain performance. Initially, they are to be achieved completely independently of the result and are the basis for achieving a certain result in the first place. According to our observation, people and managers jump quickly on result goals when it is a matter of achieving certain annual figures, turnover or falling pounds on the unloved scales. But without the derivation of concrete actions that realistically represent the implementation to achieve the goal, a set result target is only worth half. And thus, something for the annual wish list rather than for the list of things I am proud of.

The beautiful and important thing about action goals is that we can constantly monitor their execution. The performance targets described in the previous chapter can only be verified and measured afterwards. With action goals it is different because I myself, as a person, have a direct influence on their implementation. If I learn too little vocabulary, I will probably not improve my language skills. If I move too little, the scales will not tip in the direction I would like. If I don’t train my endurance enough, I won’t noticeably improve my time in the half marathon. I’m sure you realize where this is going: action goals are the breeding ground of our further development and personal success. The art lies in deriving them from higher-level success goals and regularly achieving them. “Constant dripping wears away the stone” is how an old proverb describes it very succinctly. Only the constant implementation and adaptation of the action goals to the exact needs will have an effect, which will then be reflected in the desired results.

2.4 Performance targets: The how

The connection, the bridge between action and the target image, so to speak, is ultimately the performance to be achieved. It is decisive for success. We have to work on it if we want to achieve a qualitative improvement in the result. It doesn’t matter whether it’s the cooperation of employees, the quality assurance of a product or the stamina of my body as an athlete: performance is made up of a multitude of concrete actions. In other words: the sum of all qualitative and quantitative actions, related to the respective context, is my visible performance.

Achievements and performance targets are therefore directly related to the overarching goal. It is of great importance that the performance goals set are always in line with this overarching concern, for example, to launch a new product on the market or to win a major tournament. Because it is precisely this actual goal, the suggested North Star as an emotional booster, that sets the path on which I now have to put together concrete “packages” in order to identify performance issues. On the way to the top, every team needs a number of these packages in order to get closer to the overall goal and to shake off the competition. These can be, for example, a flexible decision-making structure, up-to-the-minute communication or innovative production lines. In sport, one would speak of a well-rehearsed forward line, good distance shooters or technically perfect movements. They all require individually highly qualified, equal contributions in order to develop a package in teamwork that is ultimately better than that of the competition. Optimally, these performance goals are measurable in order to always have an orientation in the course and for further development. For example, the exact definition of a daily production figure within a set time could be a clearly measurable performance target.

High-performance teams have the big picture in mind

The beautiful and helpful thing about clearly formulated, meaningful performance goals that relate to something bigger is also that in real high-performance teams, formalities, vanity and one’s own status take a back seat. Instead, it is important for their members to always make the best possible contribution to achieving the team goal. This is because the focus is on concrete, measurable and tangible achievements that can only be made as a team. The following applies: only those who move can also create something that moves. Therefore, high-performance teams are mostly characterized by a high dynamic, implementation rate and contribution density, that is, quantity of actions contributed by each individual. Performance targets help to ensure that the team is always challenged. Because, it must also be said, with all the positive images of goal ideas and great visions, there is always a healthy respect for failure.

Real teams, however, do not let themselves be blocked by this, but develop a now-first-right attitude. They draw energy and drive from concrete ideas of how something can optimally lead to a certain result and thus to success. Knowing that doing nothing or inefficient time management takes them away from the goal, set goals also have the side effect of building up a certain pressure.

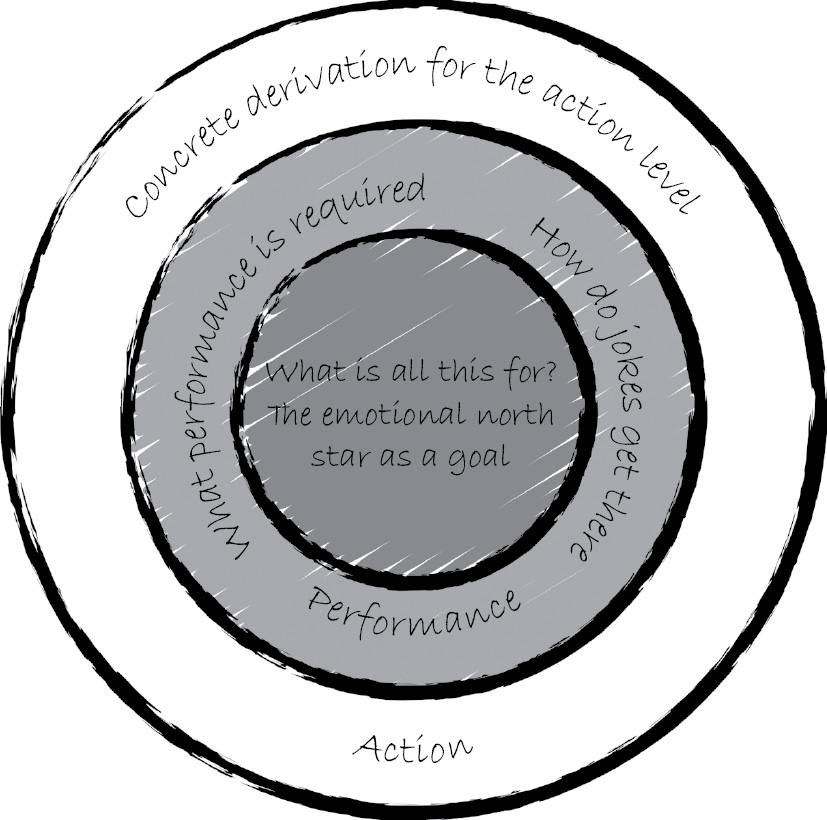

If we now combine Simon Sinek’s (1.5) approach to the Golden Circle, described in the chapter above, with our own target concepts, we come across an important message. Without a clear why, even more concretely: why, you should not make any elementary decisions in life, neither for yourself nor for others. It is not for nothing that children so often ask “Why?”, because they want to learn to understand things and to classify them for themselves. After the “why” has been clarified, the “how” question should follow. The how wonderfully describes the performance level, how exactly a certain action has an effect and how an intention is implemented. The outer level according to Sinek describes the what. Here you need a concrete idea of what exactly the result of your broken-down action is.

In the diagram, you can easily see the levels at which you can start with all kinds of projects, professional or private.

In a business context, we often rush to the external what because, for example, we have a product in mind that we would like to launch on the market. Our creativity then quickly focuses on something haptic, concretely realizable. However, we often forget the very important question of what and whom we are doing it for.

Necessary thoughts in advance are therefore: who exactly wants my product and why is mine better than the competition’s? Unfortunately, basic, seemingly banal questions are often not really answered. Why exactly this topic has to be discussed and why exactly these employees should be present at the meeting often remains the secret of the inviter. An important preliminary work is therefore to question the real (meeting) reason and to get an exact idea of the possible expectations of the participants. And this plays exactly in the inner field of the why.

In our private lives as well as in sport, we have learned: “Set yourself goals.” Every year, we set ourselves inflationary goals at New Year’s Eve or on our birthdays. We quickly jump into the middle of the circle and believe that with a quickly set goal, many things will improve and will take their course by themselves. But, unfortunately, this is wrong. Without the exact determination of the necessary (micro-)actions, goals are and remain merely letters on a piece of paper or thoughts in our head. Both are a start, but only the action steps that are necessary for me personally make the successful realization of goals also probable and thus realistic. It is true that many people underlay the where-do-I-want-to-go question with images and (apparent) answers. The deeper meaning, the actual concern, the motivational driver, however, are not clearly and honestly expressed. We leave the further examination of this playing field to colleagues like Sinek. Our focus is primarily on achieving team goals.

2.5 Interventions and a good ending

Let’s go back to Boom once again. The German hockey men travelled to Belgium without a clear mission. They had neither a clearly elaborated goal for success nor individual work assignments in their luggage. “It’s just a European Championship, we want to win it, just like we want to win all the games.” This or something similar might have sounded like the thoughts of players and coaches, had they been made legible or audible at the time. Due to the very successful phase and the achievement of the core objectives in 2013, the coaching team had missed the opportunity to give the European Championship a common concern and thus its own “why”.

In the shark tank of competition, small differences often make a big difference. “It’s all about details”, Australian co-coach Andrew Meredith used to say. In our 2013 European Championship example, it was honestly more than details that we failed to give the team in the run-up. In a world-level tournament, up to six teams have a realistic chance of finishing at the top. It is pure competition and any mistake before or during the tournament will most likely be bitterly punished by the competition. This makes precise preparation on a tactical and emotional level all the more important. In the tournament itself, the primary focus should be on maintaining and correcting the necessary team dynamics as well as the precise tactical adjustment of the team from game to game.

However, without a roadmap, a direction, an overriding concern as a common orientation for a group of motivated individual skiers, there is simply a lack of decisive factors for a complete inner connection and bond. At least that’s how it felt to me, Stefan, as co-trainer at the time.

So, what did we do without further ado? We pressed the mood button and tried to create energy and a new “environment”. We felt the guys needed a lot more support, positive feelings and a different atmosphere from the outside. We hung national team jerseys on the ceiling in the meeting room, restructured the daily routines, strengthened team contact with each other and made a motivational film out of great game scenes and fitting dramatic music. But would that be enough? Could the failures of the previous weeks be corrected with a few games and music? Could the boys change their mode in a tournament just like that and add the missing factors? Yes, they could, and how! Their arch-rivals from the Netherlands were defeated in the semi-finals and, in the final, they got their desired revenge against Belgium and their 8,000 fans.

So, somehow we managed it, somehow the boys in particular managed it. Maybe it was the conviction of a high-performance team at that time to go to the extreme reserves of strength, mentally and physically, even at short notice. We will never know for sure. In any case, it was a roller coaster of emotions for the coaches involved, including a somewhat happy ending. But even great teams occasionally need this luck at the right time, as even data analysts agree. All’s well that ends well: in retrospect, this is completely true of this tournament on the results level. On the action level, the coaching team and the team itself did not deliver a top performance for a long time. But when it came down to it, the engine was oiled and running at full speed.

We summarize

−Every project, every undertaking that you want to produce a successful result, needs a clear, overarching concern and a detailed objective for the how and the what. Knowing where you want to go is one thing, knowing how to get there is another.

−The goals of the people involved are individual and not always identical. Recognizing this and dealing with it is part of leading a high-performance team.

−Always adjust goals according to the context. Pursuing unrealistic goals is simply a waste of time.

−Break down goals into individual, comprehensible actions. This makes them tangible for your team.

Time-out: Expert interview with Prof. Dr Gerald Hüther

Gerald Hüther is considered Germany’s best-known brain researcher and is a multiple best-selling author. Practically, he is involved in neurobiological prevention research within the framework of various initiatives. He writes non-fiction books, gives lectures, organizes congresses, works as a consultant for politicians and entrepreneurs and is a frequent guest on radio and television. He studied and researched in Leipzig and Jena, then at the Max Planck Institute for Experimental Medicine in Göttingen from 1979. He was a Heisenberg Fellow of the German Research Foundation and was Professor of Neurobiology at the University of Göttingen from 2004 to 2016. From 1994 to 2006, he headed a research department he established at the psychiatric hospital in Göttingen.

Dear Gerald, we are pleased to be able to use your experience, especially for the topic of a common concern in teams. You are an absolute leader for us in Germany. Thank you very much!

Our readers know you from numerous formats, including the film The Quiet Revolution, which is about making decisions in leadership contexts. Where exactly does brain research find its practical place here?

Gerald Hüther: Our brain is inseparably connected to the rest of our body, and the neuronal circuits that guide our thinking, feeling and acting are formed by the experiences we have with our body and in relation to other people. Therefore, the inner organization and functioning of the brain cannot be understood as long as it is studied in isolation from these physical and social circumstances. Leaders, too, often have formative experiences with their bodies and with other people at a very early age. If they themselves do not understand why they have become the way they are, they will be even more unable to understand their employees.

Details

- Pages

- Year

- 2022

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781739809256

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781739809256

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781739809249

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2022 (October)

- Keywords

- Building teams managing teams role clarity high performance teams successful team organization business